Ohio River Bridges Project commits Metro Louisville to an unjust and polluting regional transportation plan

“The Kentuckiana Regional Planning and Development Agency (KIPDA) provides regional planning, review, and technical services for the Louisville Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO), and is often referred to as being the Louisville MPO. The Louisville MPO serves the following counties: Oldham, Bullitt, and Jefferson in Kentucky; Clark, Floyd, and 1/10th of a square mile of Harrison in Indiana.”

http://www.kipda.org/Transportation/MPO/TPC.aspx

The Transportation Policy Committee (TPC) carries out key policy functions and directs the transportation planning process for the Louisville (KY-IN) Metropolitan Planning Area (MPA) in accordance with the Federal Transportation Act, SAFETEA-LU. Such responsibilities include cooperative transportation planning and programming, including the review and approval of appropriate plans, implementation programs, and other similar items.

The chief elected official of each unit of local government within the MPA that is represented on the KIPDA Board of Directors is a voting member of the TPC. In addition to elected officials, the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet Secretary, the Indiana Department of the Transportation Commissioner, the Indiana Department Chief of Transportation Division, the Chair of the Transit Authority of River City Board of Directors, and other officials and agencies as agreed by the TPC are voting members. Non-voting, or advisory members, are added or deleted as agreed by the TPC. The TPC is a forum for developing consensus on policy actions among the various jurisdictions.

Right: The 2012 KIPDA membership is shown. The roster includes members of the industrial lobbying group-GLI, indicative of the pro-growth business capture of the planning organization.

See the KIPDA home page: <http://www.kipda.org/>

There is no board member from the environmental organizations though such a position would soon be occupied by a pliant, token representative --of which many abound.

Congress decreed the structure and membership of MPOs in 23 USC § 134(d) :

(d) DESIGNATION OF METROPOLITAN PLANNING ORGANIZATIONS.—

-

(2)STRUCTURE.—Each metropolitan planning organization that serves an area designated as a transportation management area, when designated or redesignated under this subsection, shall consist of—

(A) local elected officials;

(B) officials of public agencies that administer or operate major modes of transportation in the metropolitan area; and

(C) appropriate State officials.

CHANGE THE LAW

This law needs to be changed because putting elected municipal officials in charge of regional transportation planning means good science falls under the wheels of politics.

Mayors and County Judges are the top leaders in Democratic or Republican political machines engaged in a money hungry, gloves off, fight for elected offices. Local politicians are too sensitive to the demands of the monied interests who are also major campaign donors. The campaigning politicians bring their electability concerns to the role of regional transportation planning.

Concepts such as reducing global warming, implementing long term sustainability, transitioning to low fuel consumption transit alternatives, and correcting social injustice, upset local marketplace relationships and cannot be tolerated. Politicians will never be planners that say ‘no’ to powerful car dealership lobbies, engineering contractors and concrete suppliers--the backbone of the municipal economy. Politicians cannot survive an election with a green agenda or one that places future sustainability above current business plans.

The adopted Horizon 2030, when finally built will leave west end Louisville without effective affordable transit to jobs being created in the east end. The regional plan is auto dependent and based on the idea that future workers will be able to afford auto loans, auto insurance, four dollar a gallon or higher gasoline, as they commute long distances across the county to jobs.

The May 21 Connecting Kentuckiana KIPDA public consultation meeting at the Science Museum was a bust. The planning agency’s regional plans resulting in the Bridges Project, will demand that Kentuckians fork over at least $2.9 billion dollars out of their pockets. But on May 21, most folks either weren’t aware the agencies potent decisions were offered for comment, or they couldn’t break away from working a second job to show up and complain.

Kentuckians have a lot to lose if Connecting Kentuckiana becomes a stealth public outreach program that comes and goes with little public participation. There is a lot wrong with the KIPDA Planning agency--as I point out below--and the resulting regional transportation plan will channel the economic activity of the region, making some areas winners and some areas ghettos.

The public consultation process in this vastly important planning process is being flashed through town with insufficient media support resulting in the empty room on May 21 where I was the lone commenter for a half hour. I was very cordially treated by the KIPDA staff, who encouraged my comments and took notes based on my mark up of a good regional map.

My chief complaint about the public outreach process was that it should be preceded by publication on the web of a ‘State of the Regional Transportation Plan’ document. The general public is fairly clueless about regional transportation planning and its impact on neighborhoods, commercial activity, air and water pollution, and where we are headed if gasoline suddenly increases in price.

The Connecting Kentuckiana must be supported with TV media and KIPDA should ask the TV stations for a minute on the news programs to make a public service pitch for folks to come out. Nobody did on May 21.

Regional Transportation Planning

Public participation and comment processes conducted by state agencies have devolved into a managed process where slick facilitators produce an appearance of the government actually giving fair consideration to the ideas offered by the public.

But, when billions of dollars of engineering contracts are at stake, cabals of political and economic actors form up to influence the process to make sure the billions spent benefit their friends and supporters.

Thus the Congressional attempt to provide by law, public oversight in regional transportation planning, pits the un-funded local citizen, against the highly funded business community, whose political donations elect the officials who manage the MPO-metropolitan planning organization.

The result in Louisville, is a regional planning organization, the Transportation Planning Committee of KIPDA, that has dispensed with light rail projects that could efficiently and sustainably move commuters to jobs and markets around the area. The powerful automobile lobby here has far more influence with the MPO than proponents of public transit.

“If social capital is the basis for cooperation and coordination in a network,” Vogel and Nezelkewicz argue, “then the cultural and regional divisions in the Louisville metropolis may indeed be the problems facing the MPO. Building social capital requires creating stronger ties among regional citizens and actors. Trust results from sustained interaction and dialogue.” (p. 128).

CART, a proponent of regional light rail, engaged in numerous public consultation proceedings during the 90s with KIPDA and other agencies, attempting to produce strong ties between regional citizens and decision makers that would result in sound transportation planning.

Instead, a split occurred between economic development interests, and proponents of a sustainable, regional transportation system. Affordable public transit routes using light rail were discarded by the politically-appointed, KIPDA MPO decision makers. An underlying cause was privatization of the former ammunition plant in Clark County, Indiana that attracted a consensus of economic development interests and political figures at the state, local and federal level. The presence of major auto manufacturers and auto dealers associations in Louisville looking to establish supplier networks, and trucking routes along the Gene Snyder freeway corridor, caused further marginalization of public transit proponents and destroyed their influence with decision makers.

§ 134. Metropolitan transportation planning

(a) POLICY.—It is in the national interest to—

(1) encourage and promote the safe and efficient management, operation, and development of surface transportation systems that will serve the mobility needs of people and freight and foster economic growth and development within and between States and urbanized areas, while minimizing transportation related fuel consumption and air pollution through metropolitan and statewide transportation planning processes identified in this

chapter; and

(2) encourage the continued improvement and evolution of the metropolitan and statewide transportation planning processes by

metropolitan planning organizations, State departments of transportation, and public transit operators as guided by the planning factors identified in subsection (h) and section 135(d).

(c) GENERAL REQUIREMENTS.—

(1) DEVELOPMENT OF LONG-RANGE PLANS AND

TIPS.—To accomplish the objectives in subsection

(a), metropolitan planning organizations designated under subsection (d), in cooperation with the State and public transportation operators, shall develop long-range transportation plans and transportation improvement programs for metropolitan planning

areas of the State.

(2) CONTENTS.—The plans and TIPs for each

metropolitan area shall provide for the development

and integrated management and operation of transportation systems and facilities (including accessible pedestrian walkways and bicycle transportation facilities) that will function as an intermodal transportation system for the metropolitan planning area and as an integral part of an intermodal transportation system for the State and the United

States.

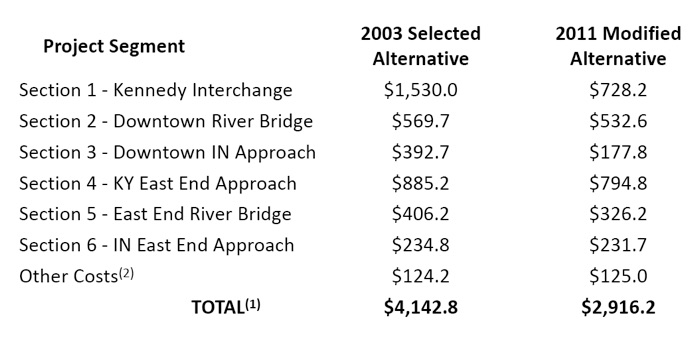

The 2011 Modified Alternative plan for the Ohio River Bridges Project will cost more than $ 2.916 Billion and is concrete multi-lane bridges and approaches for gasoline fueled automobiles.

As a sop to transit, $ 20 million, .7 %, will buy TARC some new buses, but the cash strapped agency will have to operate and maintain them on its own dime.

2012 KIPDA BOARD OFFICERS

The Honorable Sherry Conner, Chair

Mayor of Shively

The Honorable John Logan Brent, Vice-Chair

Henry County Judge/Executive

The Honorable Jeff Gahan, Secretary/Treasurer

Mayor of New Albany

The Honorable Rob Rothenburger, 2011 Chair

Shelby County Judge/Executive

KIPDA BOARD MEMBERS

BULLITT COUNTY, KENTUCKY

The Honorable Melanie Roberts

Bullitt County Judge/Executive

Ms. Debby Carter

Truck America Training, LLC

CLARK COUNTY, INDIANA

The Honorable Robert Hall

Mayor of Charlestown

The Honorable Les Young

President, Clark County Board of Commissioners

The Honorable John Gilkey

President, Clarksville Town Board

The Honorable Michael Moore

Mayor of Jeffersonville

FLOYD COUNTY, INDIANA

The Honorable Steve Bush

President, Floyd County Commissioners

HENRY COUNTY, KENTUCKY

The Honorable Jason Scriber

Property Value Administrator, Henry County

JEFFERSON COUNTY, KENTUCKY

The Honorable Greg Fischer

Mayor of Louisville

The Honorable Bill Dieruf

Mayor of Jeffersontown

The Honorable Bernard Bowling, Jr.

Mayor of St. Matthews

Ms. Eileen Pickett, Executive Vice President

Greater Louisville, Inc.

JEFFERSON LEAGUE OF CITIES

The Honorable Byron Chapman

2010 Chair

MINORITY-AT-LARGE

Ms. Karen Blake

Shelby County Fiscal Court

OLDHAM COUNTY, KENTUCKY

The Honorable David Voegele

Oldham County Judge/Executive

The Honorable John Black

Oldham County Deputy Judge/Executive

SHELBY COUNTY, KENTUCKY

The Honorable Tom Hardesty

Mayor of Shelbyville

SPENCER COUNTY, KENTUCKY

The Honorable Bill Karrer

Spencer County Judge/Executive

The Honorable David Goodlet

Magistrate, Mt. Eden

TRIMBLE COUNTY, KENTUCKY

The Honorable Randy Stevens

Trimble County Judge/Executive

The Honorable Nolan Hamilton

Magistrate, District 1, Trimble County

KIPDA LEGAL COUNSEL

Mr. Frank Chuppe

Wyatt, Tarrant & Combs

Scenes from the KIPDA Connecting Kentuckiana Public outreach meeting at the Science Museum on 5-21-2012. Few members of the public attended. Larry Chaney, standing, Director of Transportation on the KIPDA staff in the lobby at the museum

Bright and fluffy slide show plays on a five minute loop to an empty room. Transportation planners were on hand and gave very good discussion of the KIPDA region on maps and assisted in making public comments.

One of the comments I made was that the K&I Bridge should be rehabilitated to include a light rail connection to New Albany. This idea has been floated by CART member, Steven Greseth, and the KIPDA planners seemed supportive.

See more HERE

The decision at hand

The problem of economic development interests prejudicial stranglehold on the political actors overseeing regional transportation planning, has produced an immediate challenge:

Imminent adoption of $ 2.9 billion modified selected alternative in the Ohio River Bridges Project scheduled to be final with an ROD in June, 2012.

Historical Perspective on regional transportation planning

“The ORMIS process has avoided a broader discussion of regional growth and how the location of the bridge may spur more suburbanization or hinder center-city revitalization. Instead, the focus has been on the need for a bridge to alleviate traffic congestion and the potential to facilitate economic development”

Vogel, Ronald K., and Norman Nezelkewicz. 2002. Metropolitan planning organizations and the new regionalism: The case of Louisville. Publius: The Journal of Federalism 32, 1 (Winter): 107-

129.

“In a recent analysis of the ORMIS process, Vogel and Nezelkewicz (2002) claim that the key to understanding the TPC’s decisions, especially with regard to building two new bridges, is knowing that key political actors had taken fixed (and divergent) positions on the bridge issue before the MIS process even began. Once ORMIS proposed specific sites, they say, consensus about regional transportation planning began breaking down.

The central question this raises is: where is the African-Americans’ voice and story in the very technical and highly bureaucratized effort to plan the transformation of the region’s transportation system? To judge by Vogel and Nezelkewicz’s analysis, their voice and story has been translated into political interests and technical terms such as origin/destination, modal choice, and vehicle trips per day. Because their voice is so weak relative to that of economic development interests and middle class exurbanites, Louisville’s African-American population finds itself not well served by the city-region’s transportation planning process.

“If social capital is the basis for cooperation and coordination in a network,” Vogel and Nezelkewicz argue, “then the cultural and regional divisions in the Louisville metropolis may indeed be the problems facing the MPO. Building social capital requires creating stronger ties among regional citizens and actors. Trust results from sustained interaction and dialogue” (p. 128). Moreover, the fact that Norton Commons will be virtually inaccessible except by private auto reveals the poor coordination between transportation and land use planning at the city-region scale.”

Where Muhammad Ali Learned to Fight: Inventing a Sustaining Myth for a Place Called Louisville by James A. Throgmorton, Graduate Program in Urban and Regional Planning, The University of Iowa Chicago Cities Conference 2005

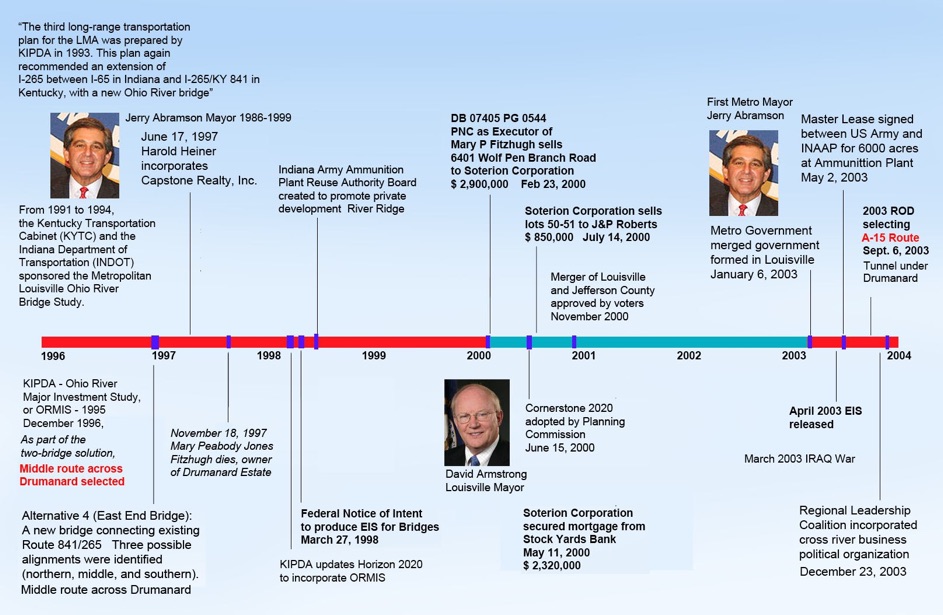

Correcting historic discrimination by providing new affordable rapid transit from west Louisville to job centers in east and south Louisville should have been central to regional planning. But, instead the commitment of more than $ 2.9 billion dollars in transportation spending that doesn’t even recognize the lost opportunity smacks of intentional racism and will have the effect of continuing race segregation and economic disparity.

The obligations under Title VI are dealt with by conceding that tolls on the bridges may have some disparate impact on low income minorities. but not that the whole plan is warped.

“The environmental justice evaluation in this SFEIS focuses on modifications that have occurred in the basic design of the Modified Selected Alternative and the potential effects associated with tolling—as described in the two subsections below. The primary concerns identified as a result of this evaluation are the potential direct economic impact on environmental justice populations as a result of the institution of tolls on the new Ohio River bridges, and potential indirect effects on environmental justice communities as a result of changes in traffic patterns caused by tolling.

5-34

It is important to note that the existence of an impact does not necessarily mean that the impact is “disproportionately high and adverse.” That is, an impact must be both adverse and disproportionate in order to be considered an environmental justice impact. According to FHWA policy, in order to constitute an environmental justice impact, an effect must be adverse, and it must either be “predominantly borne” by a minority or low-income population, or the effect on the minority or low-income population must be “appreciably more severe or greater in magnitude” than the adverse effect on the non-minority or non low-income population.

5-37

The calculations demonstrate that in general, and as one would expect, a low-income person who uses the bridges for a daily commute would have more of their annual income used for tolls than non low-income populations using the bridges. However, in considering this data, it is important to note that, according to the survey results described above, only 10% of low-income vehicle users reported that they currently use the Ohio River crossings on a daily basis.

Therefore, a relatively small percentage of low-income users would experience the cost of daily bridge tolls.

Though it is not expressly discussed as a Title VI impact, the FSEIS contains documentation that west and south end Metro residents will not enjoy the benefits of the massive economic expansion triggered by the building of the East End Bridge.

"Therefore, the 2030 forecasts for the FEIS Selected Alternative and the Modified Selected Alternative, which include the construction of the Downtown Bridge and the East End Bridge,

reflect greater population and employment growth within a 10-mile radius of the downtown area than would the No-Action Alternative. In addition, these two alternatives are also forecasted in 2030 to result in less population and employment growth in the portion of the region beyond the 10-mile radius of downtown Louisville in comparison to the No-Action Alternative. The

forecasted population and employment figures show that more of the region’s overall growth would shift slightly beyond downtown Louisville as a result of the construction of the proposed project and the anticipated residential and commercial growth associated with the project. As indicated in tables 5.1-4 though 5.1-5, the percentage change is minor (i.e., up to 4% difference)."

Supplemental Final EIS 5-5 Chapter 5—

Environmental Consequences

This vague analysis completely obscures the shift is

to the east away from the Title VI area nor does it

calculate the impact of the shift.

Economic Impact Study of the

Ohio River Bridges Project,

by the Economic Development

Research Group Prepared for:

Indiana Finance Authority

One North Capitol, Suite 900,

Indianapolis, IN 46204

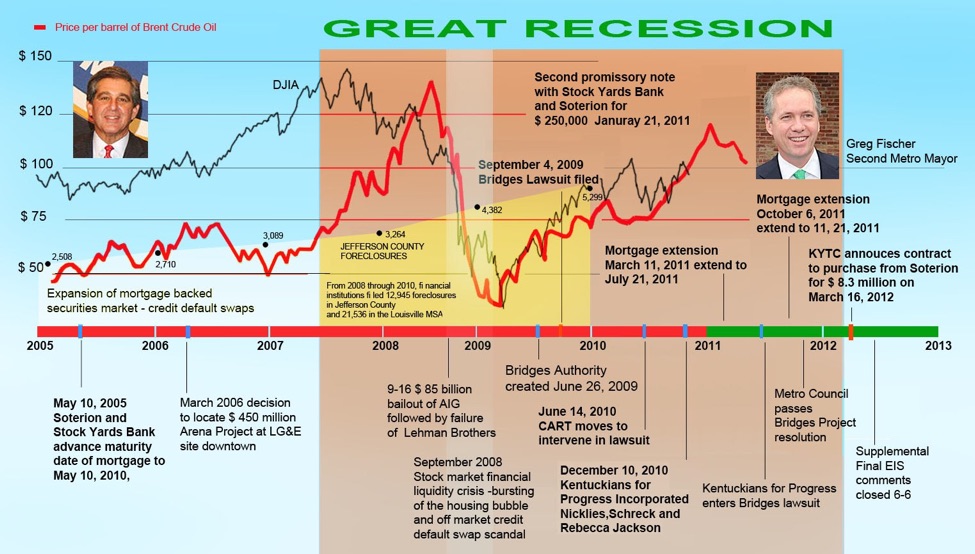

In this map from the FSEIS areas of job growth

predicted as a result of the Bridges Project are shown

in red areas, where job loss is in blue.

Page 3

The majority of the contingent development impacts

in Indiana will be located in eastern Clark County in

the vicinity of the Port of Indiana and the River Ridge

Commerce Center. The planned East End Bridge will

directly serve these two unique facilities.

Kentucky hasn’t conducted an economic impact study

because the state doesn’t require them for road

projects, said Chuck Wolfe, a Transportation Cabinet

spokesman.

Paul Coomes, a University of Louisville economist,

said it’s “unfortunate” that the Indiana study

didn’t look at the economic impact in Kentucky.

Supplemental Final Environmental Impact Statement

It did, however, estimate that the Louisville area would

have 803,844 jobs in 2030 and that, if the project

were built, about 12,000 of those jobs would be

created in Clark and Floyd counties.

If the project weren’t built, they would have located

in Jefferson and Oldham counties, the study says.

FSEIS 5-23

Relative Employment Impacts – Year 2030

Build vs. No-Action

Jefferson County (6,187)

Bullitt County 0

Oldham County (5,800)

Clark County 8,790

Floyd County 3,197

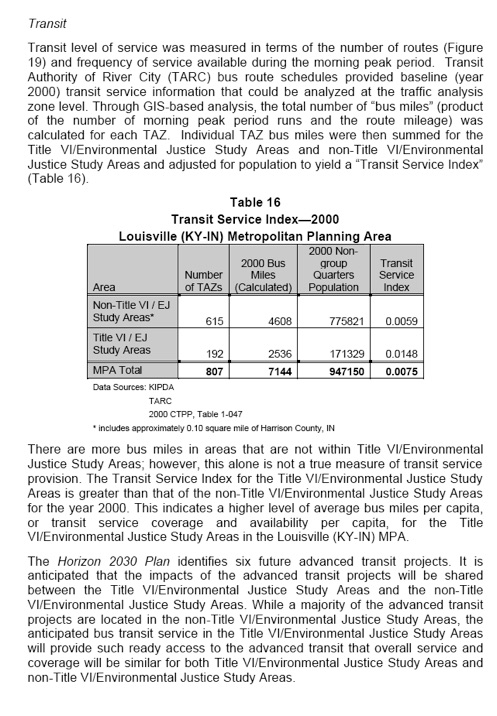

Right: Map of the low income minority segregated

area of West Louisville and Newburg. These areas

have high unemployment and are isolated by slow

TARC connections for public transit. Sprawl

development in the east end will produce warehouse

jobs 10 to 12 miles from Title VI area.

Historic discrimination

“According to the 1950 census, since the start of the war, the city's population had grown by nearly sixteen percent to 369,000, of whom 15.7 percent had been classified by census officials

as "nonwhite."

That population was becoming increasingly segregated following white flight to the suburbs that began in the 1930s and accelerated in the 1950s. As a result, African Americans became

concentrated in the oldest and most crowded sections of the city's west end. The population growth resulted in part from

an expansion of war-time defense industries that drew workers to the city, a resurrection in the local economy that began in Louisville's chemical, plastics, and munitions factories. This

expansion continued after the war so that, by 1950, thirty-one percent of the population worked in manufacturing. African Americans, however, did not share equitably in the new jobs. A study by two social scientists at the University of Louisville showed that in 1950 sixty-two percent of white men worked in white collar, skilled or supervisory positions while the same percentage of black men labored in service jobs or unskilled positions. Hence, these manufacturing plants helped shape not only the city's economic growth but, indirectly, its racial climate.”

Tracy E. K’Meyer, The Gateway to the South: Regional Identity and the Louisville Civil Rights Movement, Ohio Valley History, Volume 4, Number 1, page 44, Spring 2004. ( Citing, Scott

Cummings and Michael Price, Race Relations in Louisville: Southern Racial Traditions and Northern Class Dynamics, Urban Research Institute Policy Paper Series June 1990, 13.)

The too narrow Title VI analysis as stated in the SFEIS

A carefully crafted Purpose and Need Statement framed the planning process in a way that allowed the economic elite to pursue approval of their pre-selected two bridges alternative.

The purpose and need has been sterilized to remove any reference to the grinding poverty and race discrimination suffered in the west end of Louisville. Thus revitalizing the low income and minority area of the west end does not appear as a recognized item in the adopted Purpose and Need statement. This is a reflection of the overwhelming white, upper income membership of the TPC.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and subsequent laws passed to implement the Act are supposed to require transportation planning that does not result in disparate impact or denial of benefits of federally funded transportation projects based on race. But the Bridges Project planners have defined this major Metro Louisville race problem right out of consideration by eliminating it from the Purpose and Need Statement.

See SOCIAL JUSTICE page HERE

Purpose and Need (excerpted from the SFEIS)

The original Purpose and Need statement, documented in the FEIS, has been revalidated through an update of the supporting data

(See SDEIS Appendix A.1, Purpose and Need White Paper).

The preliminary analysis leads us to recommend that the purpose of the proposed project should remain unchanged from the original EIS, which was to improve cross-river mobility between Jefferson County, Kentucky and Clark County, Indiana.

Specific factors demonstrating the continuing purpose and need for this project include:

• Inefficient mobility for existing and planned growth in population and employment in the Downtown area and in eastern Jefferson and southeastern Clark Counties;

• Traffic congestion on the Kennedy Bridge and within the Kennedy Interchange;

• Traffic safety problems within the Kennedy Interchange and on the Kennedy Bridge and its approaches;

• Inadequate cross-river transportation system linkage and freeway rerouting opportunities in the eastern portion of the Louisville Metropolitan Area;

• Locally approved transportation plans that call for two new bridges across the Ohio River and the reconstruction of the Kennedy Interchange.

Page 15 SEIS Mass Transit Alternatives

The following Mass Transit Alternatives were evaluated as separate alternatives:

• Rail Transit - Rail transit would generally travel from north of I-265 in Indiana, to downtown Jeffersonville, then across the river to downtown Louisville and destinations south of downtown Louisville. Rail connections between Indiana and downtown Louisville were previously considered during the ORMIS study and have also been studied by TARC.

• Enhanced Bus Service - Potential options for enhanced bus service include the addition of new service, increasing the frequency of existing service, or providing travel time advantages for transit. New service would provide an alternative for trips where transit is currently not an option. Increasing the frequency of service and providing travel time advantages would improve the competitiveness of transit by reducing waiting time and travel time. Travel time advantages may be provided by signal preemption, priority for transit vehicles, or dedicated travel lanes for transit vehicles.

Page 23

• Transportation Demand Management (TDM), Transportation System Management (TSM), Transportation Management (TM), and Mass Transit Alternatives

These alternatives would not meet the purpose and need of the project and therefore would not be reasonable alternatives. These alternatives would not meet the purpose and need because

• they would not improve the geometrics of the Kennedy Interchange and Kennedy Bridge to meet American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) recommended minimum design guidelines as to meet the project’s identified safety needs, and

• they would not provide a cross-river connection in the east end to provide the needed system linkage.

In addition, while these alternatives may yield some operational benefits, they are

• highly unlikely to have any significant impact on reducing vehicle hours of delay (VHD) in the Louisville Metropolitan Area (LMA).

October 2007

Initial funding plan for Ohio River Bridges Project

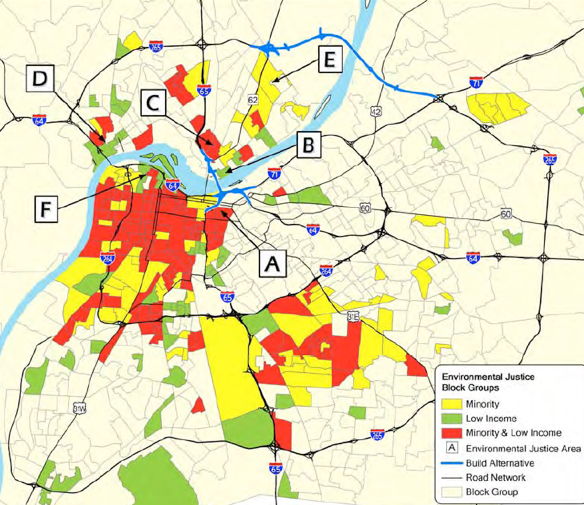

Timeline: Regional Transportation Plan

Title VI and the Ohio River Bridges Project

• the disparate impact to Title VI areas caused by investing $ 2.9 billion in the Project (facially neutral policies or practices that have the effect of disproportionately excluding or adversely

affecting members of a group protected under Title VI, or perpetuating the effects of prior discrimination based on race)

-

•the insufficiency of planned enhanced TARC routes to address disparate impact

-

•the insufficiency of the project managers Title VI analysis based solely on bridge tolls

-

•the impact of proposed and previously funded mitigation projects

Title VI

“Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is a non-discrimination statue. Specifically, Title VI provides that "no person in the United States shall, on the ground of race, color, or national

origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance."

(42 U.S.C. Section 2000d).

Each Federal department and agency which is empowered to extend Federal financial assistance to any program or activity, by way of grant, loan, federal personnel, or any federal agreement contract is authorized and directed to effectuate the provisions of Section 2000d of this title.”

“Specifically prohibited discriminatory practices in federally assisted programs include, but not limited to, the following:

• Denial to an individual of any service or benefit provided under the program.

• Distinctions in quality, quantity, or manner in which the benefit is provided.

• Disparate impact or separate treatment in any of the programs providing services to individuals.

• Different standards or requirements for benefits or participation in services provided.

• Discrimination in any activities/programs conducted in a facility built in whole or in part with Federal financial assistance.

• Methods of administration which directly or through contractual relationships would defeat or substantially impair the accomplishment of effective nondiscrimination.”

Light rail eliminated in 2003 and again 2009-2012

Light rail transit routes have been cast aside by KIPDA in the Regional Transportation Plan, and also in the Ohio River Bridges Mega- Project.

Funding was cut for the promising T2 light rail project in 2002 as political support developed for the ORMIS plan for two bridges.

Light rail transit was superficially considered but eliminated in the 2003 ROD and that same decision was reaffirmed in the 2012 FSEIS. The elimination came as a result of the overly narrow purpose and need analysis that eliminated any need to address segregation in the Title VI area as an element of regional planning. By default, the chief elements in the Purpose and Need became moving more cars and trucks across the river to serve east end growth.

If Title VI had been a component of regional planning the possibility of restoring the K&I Bridge to public transit might have been considered. The K& I carries heavy freight trains of the Norfolk Southern rail line and has two idle decks that could be rehabilitated to form a cross river corridor for Portland and the West End to New Albany, Indiana. This relatively low cost alternative has never been considered by the TPC.

Transportation Enhancement funds were used to fund the African American Heritage Center at 18th and Muhammad Ali. Some $ 20 million was expended in a boondogle that was to have built a world-class African American Heritage museum and shopping center in the historic trolley repair shed at the site. Due to cost overruns and mismanagement the building is usually empty except for occasional fetes. The exhibits designed to show the African American experience in history in Louisville were partly built but never installed. This sad chapter has deprived the area of an economic attractor and an important education site.

More Transportation Enhancement funds were deployed to start a historic property rehabilitation training program for local people. That program too, is defunct.

Judicial Action under NEPA

Because CARTs participation in public dialogue was not able to break the strangle hold of the automobile lobby and achieved nothing of its major goals, and because the economic development interests influence on decision makers has become exclusive, CART sought justice through joining the federal lawsuit filed to challenge the 2003 ROD in the Bridges Project.

CART has an immediate challenge to oppose the Bridges Mega Project modified selected alternative as

-

•not good for regional transportation planning,

-

•not good for long term sustainable development

-

•not good for social justice

Compliance with NEPA is usually found:

Under the Administrative Procedures Act, the agency's [FHWA and EPA] decision [approving the Bridges Project EIS] may be set aside only if it is " arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law." 5 U.S.C. § 706(2)(A).

In making the determination concerning whether an agency decision was " ‘ arbitrary or capricious,’ the reviewing court ‘ must consider whether the decision was based on a consideration of the relevant factors and whether there has been a clear error of judgment.’ " Marsh v. Oregon Natural Resources Council, 490 U.S. 360, 378, 109 S.Ct. 1851, 104 L.Ed.2d 377 (1989) (quoting Citizens to Preserve Overton Park, Inc. v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402, 416, 91 S.Ct. 814, 28 L.Ed.2d 136 (1971)).

Under NEPA's applicable regulations, a federal agency's EIS must " [r]igorously explore and objectively evaluate all reasonable alternatives [to a proposed action], and for alternatives which were eliminated from detailed study, briefly discuss the reasons for their having been eliminated." 40 C.F.R. § 1502.14(a).

We have repeatedly recognized that if the agency fails to consider a viable or reasonable alternative, the EIS is inadequate. See e.g. Friends of Yosemite Valley v. Kempthorne, 520 F.3d 1024, 1038 (9th Cir.2008); 'Ilio'ulaokalani Coalition v. Rumsfeld, 464 F.3d 1083, 1095 (9th Cir.2006).

HISTORY OF METROPOLITAN PLANNING ORGANIZATIONS

<http://www.ampo.org/content/index.php?pid=15>

“The decade of the 1980's [President Reagan] ushered in a new mood in the nation to decentralize control and authority, and to reduce federal intrusion into local decision making. The joint FHWA/UMTA urban transportation planning regulations were rewritten to remove items that were not specifically required by statute. The new regulations required a transportation plan, a transportation improvement program (TIP)including an annual element, and a unified planning work program for areas of 200,000 or more in population. The planning process was to be self-certified by the states and MPOs as to its conformance with all requirements when submitting the TIP. Essentially, only the end products were specified while the details of the process were left to the states and MPOs.

“This represented a major shift in the evolution of urban transportation planning. The result was an urban transportation program and process that languished, and the loss of much of the technical capacity that has been built up in the MPOs.”

ISTEA reversed the trend of deterioration with its renewed emphasis on the metropolitan transportation planning process. The legislation was designed to put in place a framework to guide the operations, management and investment in a surface transportation system that is largely in place. ISTEA strengthened the metropolitan planning process, enhanced the role of local elected officials, required stakeholder involvement, and encouraged movement away from modal parochialism toward integrated, modally mixed strategies for greater system efficiency, mobility and access.”