East End Bridge: Flawed bridges plan puts east end bridge route over LWC drinking water intake

© 2011 Louisville, KY Bud Hixson

East End Bridge: Flawed bridges plan puts east end bridge route over LWC drinking water intake

© 2011 Louisville, KY Bud Hixson

Welcome to BadwaterJournal.com INDEX PAGE for all articles

Severe water quality impacts to Harrods Creek may be expected in the area where the East End Bridge drains into the creek at River Road.

“While salts from roadway de-icing are not remov-able with the treatment vault, the salts would, instead of draining into the well-head protection area, be diluted by storm discharge, emptied directly into Harrods Creek, being diluted and flowing into the Ohio River. . .”

John Stacksteder, P.E.

Project Manager

Community Transportation Solutions

The pot of gold at the end of the East End Bridge CLICK HERE

The complete Supplemental Draft Environmental Impact Statement can be downloaded from the Kentucky Indiana Ohio River Bridges Project website. See new drawings below. The EIS is required by federal law NEPA Act that requires careful analysis of social and environmental impacts caused by federally funded highway projects. It also requires federal agencies to engage the public in consultation. Comments are due on January 9th. Go to:

OPEN RECORDS REQUEST -

RESPONSE TO DATA

Louisville Water Company

Barbara Dickens, Esq.

Vice President, General Counsel

& Official Custodian of Records

Beverly Soice

Re: Open Records Request 12-27-2010

by email and letter

Copy to:

John Sacksteder, Project Manager

Community Transportation Solutions

General Engineering Consultant (CTS-GEC)

Forum Office Park III

305 N. Hurstbourne Parkway, Suite 100

Louisville, KY 40222

DEP Division of Water

200 Fair Oaks Lane

Fourth Floor

Frankfort, KY 40601

Ted Pullen

Metro Public Works & Assets

444 South Fifth Street

Suite 400

Louisville, KY 40202

Beverly Soice,

Thanks for your courteous response to my Open Records Request. This is a follow up

memo to our appointment, 1-14-2011 at 2:00 pm in the Kentucky River Room. Please forgive

this long post, but I need to set forth my concerns/request with some supporting documentation.

The materials provided to me so far do not establish that the Louisville Water Company

has quantified or projected the effect of groundwater contamination that will be caused by a proposed east end bridge along the A-15 route identified in the 2003 Rule Of Decision for the Bridges Project.

The materials do not indicate that LWC is taking sufficient action to protect groundwater in the WHPA from deicing contamination.

As such, it appears Louisville political leaders and citizens are not being fully and accurately informed

about the threat of road salt salinization of the ground water resources that are critical supply for Louisville's drinking water intake at the $55 million dollar artesian well collections area. Without full and complete information the public and decision makers could elect to place a six lane highway and bridge over the wellhead protection area resulting in the contamination and loss of the drinking water source and waste of $ 55 million dollars invested.

You represented at the meeting in the Kentucky Room that LWC had no groundwater protection monitoring chloride results from the Well head protection area, the WPA zones at the Payne collection area. You provided copies of Na+ (SODIUM) and chloride results for testing performed from 2006 to 2008 at the Zorn Avenue facility.

Examination of that data shows a cumulative increase over the testing period, at water monitoring wells designated ZMW-9A, 9B, 9C. At ZMW-9A.

Chlorides increased over the period September 2006 to March 2008, from 4900 mg/L to 8700 mg/L.

"There is no maximum contaminant level (MCL) or health advisory level for sodium; however, there is a

Drinking Water Equivalent Level of 20 mg/L (a non-enforceable guidance level considered protective against non-carcinogenic adverse health effects). Chloride, for which EPA has established a national secondary drinking water standard of 250 mg/L, adds a salty taste to water and corrodes pipes. It can also cause problems with coagulation processes in water treatment plants. The water quality standard for chloride is 230 mg/L, based on toxicity to aquatic life."

Source Water Protection Practices Bulletin, Managing Highway Deicing to Prevent Contamination of DrinkingWater, USEPA, EPA 816-F-09-008 July 2009, Office of Water (4606).

I was not provided a location for the Zorn ZMW 9A site but I assume it was close to River Road intersection and sensitive to road salt runoff. Does your staff have another interpretation? These Chloride concentrations exceeded U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) acute (860 mg/L) and chronic (230 mg/L) water-quality criteria.

Thus the data provided tend to support the scientific peer reviewed literature that,

"Studies have shown that road salts can accumulate in streams and ground water, persisting beyond the time of application, often into the summer months."

"The scientists have found that salt levels (chloride and sodium) at Minebank Run are chronically elevated throughout the year, even in summer when no salts are applied. Chloride and sodium levels are significantly higher downstream of the I-695 beltway, suggesting that this major roadway is a significant source of road salts to ground and surface water in this watershed."

http://www.epa.gov/ada/eco/pdfs/road_salts.pdf

and,

"The relation of chloride concentrations and specific conductance with urban land use shown in this study and a recent study of the northern United States (23) indicates that road-salt runoff and other anthropogenic uses of chloride are importantfactors in the biological integrity of urban streams in the northern United States. Although chloride sampling has beenincluded in previous evaluations of urban streamwater quality (21), water-quality sampling did not specifically focus onperiods of winter runoff and may not fully represent the severity of road-salt influence."

Steven Corsi, et al., A Fresh Look at Road Salt: Aquatic Toxicity and Water-Quality

Impacts on Local, Regional, and National Scales, Environmental Science and

Technology, 2010, 44, 7376–7382. ACS.

This data is of particular concern to protectors of surface water quality in

Beargrass Creek if LWC intends to discharge FILTER BACKWASH at I-64 and

Grinstead Drive to the Middle Fork of Beargrass Creek.

The removal of solids from Zorn Avenue pumped water, whether derived from

the artesian collection wells or from the Zorn Avenue River intakes would

apparently leave a filtrate high in chlorides.

DATA PROVIDED

The sole document provided to me that directly referred to the object of my Open

Records request was titled, "Proposed Transportation Management Plan" on Page 10 it reads,

"Additional Transportation Issues"

"Additional Transportation Issues include the design and drainage plan for the bridge and tunnel to be constructed over the Ohio River, at least part of which will be located within the WHPA (well head protection area). At this time, details of the design for these structures are not available. LWC plans to meet with the state highway department and design engineers to discuss methods of minimizing the potential for contamination as the design progresses. The local Planning Team will be a part of this planning process."

This laconic item is not dated and appears to be an excerpt from a newer document after the 2003 - 2004 dates of the Wellhead Protection Plan.

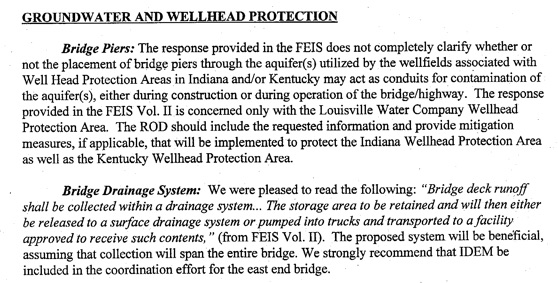

Construction of the LWC Riverbank Filtration Project began in March 2007 and was complete in the fall of 2010. The $55 million dollar investment has constructed a system that can pump up to 70 million gallons of water a day from the aquifer.

<http://www.louisvilleky.gov/LWC/News/2010/Riverbank+Filtration+Project+Completed.htm>

This tremendous drinking water supply feat of engineering deserves better protection than a sleepy note that LWC plans to meet with Transportation Dept engineers to discuss minimizing potential contamination. When would that occur? There is no statement from any qualified engineer or investigator, that a six lane superhighway is even compatible with a 70 million gallon per day drinking water well head area.

The Riverbank Filtration Project was installed after the 2003 ROD of the bridges project, and after the 2003-2004 Wellhead Protection Plan filed with the Groundwater Branch of the Division of Water.

DIFFERENCE IN WITHDRAWAL RATES USED FOR MAPS AND ACTUAL WITHDRAWAL

The 70 million gallon per day pumping rate does not seem to be a rate used by the ground water protection and well head protection plans filed with the state which show a 17 million gallon per day pump rate. The WHPP does not contain any information that the Riverbank Project could draw 70 million gallons per day. There is no indication that the community or the Planning Area Team was ever informed of corrected WHPA maps calculated to show correct areas that would result from a 70 million gallon per day draw down rate. As a result, contamination by salinity from road runoff may occur at a faster rate than indicated.

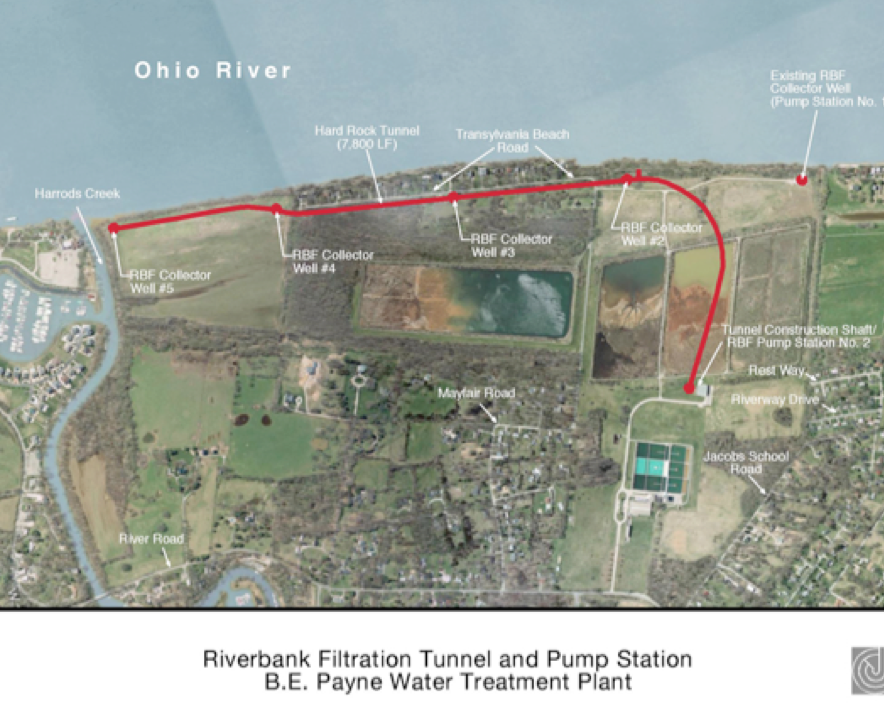

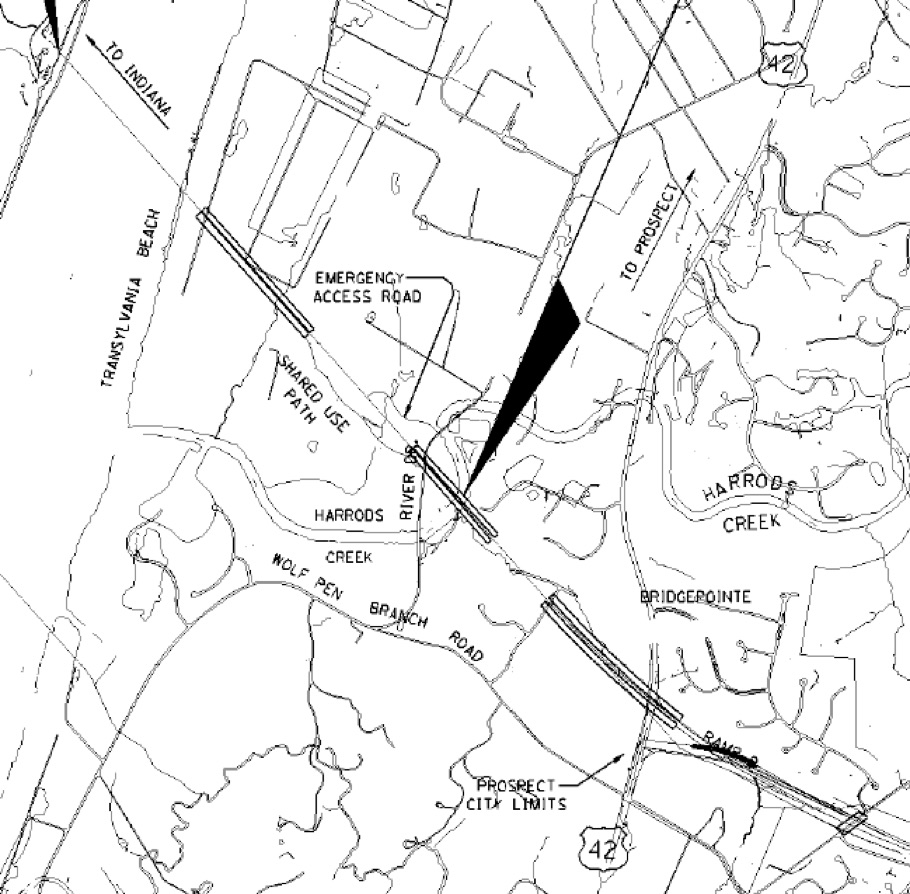

A map of the proposed route from the website <http://www.kyinbridges.com/maps-features/default.aspx?ml=4> shows the proposed route of the A-15 bridge passing directly over the wellhead protection area.

The Record of Decision discussion of the impacts to groundwater in the well head protection area is vague and unfocused as it did not contemplate the 70 million gallon per day draw down.

Nowhere is there a detailed calculation of pollutant loadings to storm water runoff from deicing

practices in the wellhead area.

Engineers projected 72,000 vehicles per day of traffic (or more) on the east end bridge

alternative. The wellhead protection plan would seem to require new expert opinion and

investigation aimed at answering the question:

How many years before bridge and highway pollution forces the LWC to shut down the

$ 55 million dollar Riverbank Filtration wells. Since the wells are linked by a tunnel, the

output of the wells would be contaminated even if only the one closest to the bridge began

to experience heavy chloride or cyanide pollution. The odds of catastrophic contamination

from toxic or hazardous chemicals hauled on the 841 connector bridge are not considered.

Neither the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet, nor the Kentucky Division of Water has the same investment of public money in drinking water facilities impacted by the proposed east end bridge

over the WHPA.

The transfer of information from your science community to the public and decision makers is

failing to fully describe the impact of road salting on drinking water resources and surface

water quality.

Please increase the information on your website to communicate this issue and the present

THREAT to the community based on your results.

Clarence Hixson

LWC Data - Test results at Zorn Avenue groundwater test wells ZMW-9A, 9B, 9C

9-19-06 Na(mg/L) Chloride (mg/L)

ZMW-9A 2900 4900

ZMW-9B 1700 2700

ZMW-9C 1600 2600

9-29-06 Na(mg/L) Chloride (mg/L)

ZMW-9A 3700 5100

ZMW-9B 1700 2800

ZMW-9C 1500 2500

10-4-06 Na(mg/L) Chloride (mg/L)

ZMW-9A 2800 5000

ZMW-9B 1800 3100

ZMW-9C 1600 2400

11-14-06 Na(mg/L) Chloride (mg/L)

ZMW-9A 3200 5300

ZMW-9B 1600 2900

ZMW-9C 1300 2400

12-13-06 Na(mg/L) Chloride (mg/L)

ZMW-9A 6900 5800

ZMW-9B 1600 2900

ZMW-9C 2800 2100

1-10-07 Na(mg/L) Chloride (mg/L)

ZMW-9A 3500 6000

ZMW-9B 1900 3000

ZMW-9C 1100 1800

2-14-07 Na(mg/L) Chloride (mg/L)

ZMW-9A 7400 6100

ZMW-9B 4300 2600

ZMW-9C 1600 2000

3-13-07 Na(mg/L) Chloride (mg/L)

ZMW-9A 3700 6800

ZMW-9B 1700 3000

ZMW-9C 1200 2100

4-10-07 Na(mg/L) Chloride (mg/L)

ZMW-9A 4000 7000

ZMW-9B 1800 3100

ZMW-9C 1300 2400

5-15-07 Na(mg/L) Chloride (mg/L)

ZMW-9A 4400 7500

ZMW-9B 1800 3000

ZMW-9C 1300 1800

6-13-07 Na(mg/L) Chloride (mg/L)

ZMW-9A 4700 7600

ZMW-9B 1900 3200

ZMW-9C 1000 1800

7-12-07 Na(mg/L) Chloride (mg/L)

ZMW-9A 4000 7100

ZMW-9B 2000 3000

ZMW-9C 1000 1700

8-14-07 Na(mg/L) Chloride (mg/L)

ZMW-9A 4300 7700

ZMW-9B 430 3600

ZMW-9C 210 1700

DATA GAP

3-24-08 Na(mg/L) Chloride (mg/L)

ZMW-9A 4900 8700

ZMW-9B 2400 4200

ZMW-9C 1600 3000

Rule of Decision

Providing information about pollution from urban storm water runoff is one of the chief goals of this website. Urban roadways are major sources of chemicals, metals and solid particles that cause local streams and rivers to become degraded.

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons-PAH, cyanide, copper, nickel, iron, sodium, chlorides, oils, carbon black, are just a few of the cancer causing, human produced products dumped on the roadways by our fleet of vehicles and washed off by the ton to receiving waters. See the Roadsalt and Tire Story pages.

The construction of a connecting bridge between the end of the Gene Snyder freeway at Brownsboro Road and across the Ohio to Utica, Indiana requires a major transfer of billions of dollars from the public to private engineering firms. Once built, the bridge will shape longterm economic development in the region drawing development away from the central core. The wealthy business elite and their workforce will no longer have to come downtown to cross to Indiana, and the focus of the local economy will continue to move east with more sprawl development degrading our last wildlife habitat and greenfields in the Floyds Fork watershed. The monied interests will force the politicians to serve their infrastructure needs in the eastern county, while the west end continues to degenerate into a ghetto of poor people.

Apart from the adverse social

justice consequences of the bridge which have not been quantified, the location of the east end approach built over the top of the Louisville Water Company artesian well collection system, poses a major risk to that multi-million dollar installation. Presently, this reviewer believes that the drinking water intakes buried in the porous sands along the Ohio River bank under the bridge and approach, will be contaminated by concentrated road runoff discharged to Harrods Creek under the current drainage and treatment plan.

INCOMPATIBLE ENGINEERING

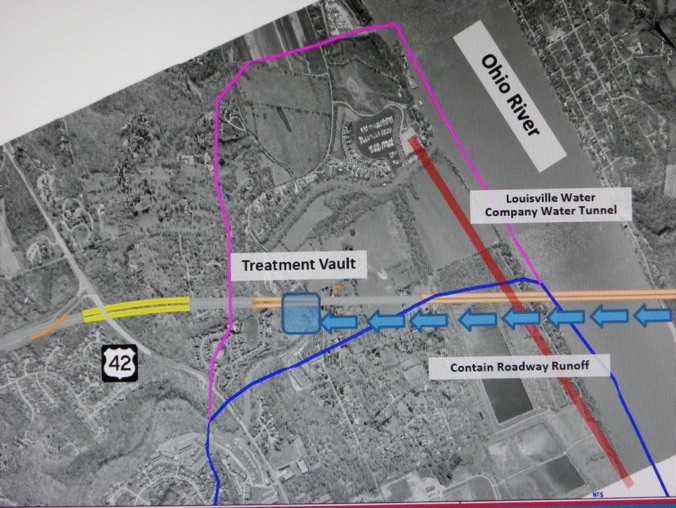

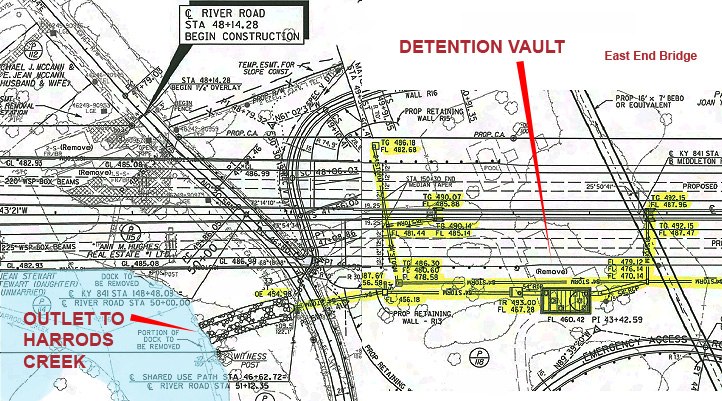

A six or four lane lane superhighway passing over a ground water protection zone would result in toxic pollution of the groundwater by automobile storm water runoff. De-icing chemicals would also pollute the groundwater if applied by the tons as the Metro Department of Public Works applies it in Jefferson County. Road salt de-icing chemicals including cyanide anti-caking compounds stay in solution and would not be removed by the swirl concentrator and filter treatment combination contained in a “treatment vault” that discharges to Harrods Creek. See engineering drawing below.

Harrods Creek flows through the well head protection area and concentrated road runoff will infiltrate into the water intake from the creek. The present treatment and discharge strategy for the east

end bridge road runoff is not protective of the drinking water source.

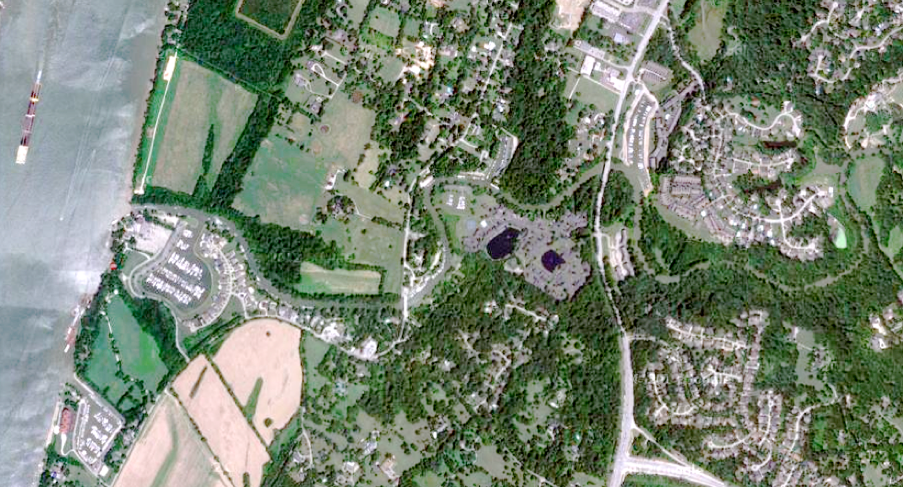

Top picture: The proposed route from the end of the Gene Snyder at Brownsboro Road across the river to Utica IN crosses over the western end of the Riverbank Filtration drinking water intake at the B.E. Payne Water Treatment Plant.

Above: The red line shows the buried connecting tunnel between the four artesian wells along the riverbank. The proposed east end bridge passes between Well # 3 and Well # 4.

By 2005, the Kentucky Division of Water and design consultants working with project lead engineering firm, H.W. Lochner, Inc. were setting up meetings to consider technical design considerations for handling bridge road runoff in the well head protection area. Section 4, Technical Meeting Summary, November 17, 2005

The sequence concept for treatment is shown in the schematic labeled Exhibit 1 from the Wellhead Protection Area and Stormwater System Design Review Meeting held at CTS on March 5, 2009. The treatment process will be capable of capturing a tanker truck spill of petroleum contaminant (about 10,000 gallons) during a rainfall event and storing the contaminant for proper disposal (case 1). SSS 5 will also be equipped with a shutdown valve that will close the outlet and store runoff up to approximately 230,000 gallons in case of a water soluble hazardous material spill during a rain event within the wellhead protection area (case 2). SSS 5 is also equipped with an overflow inlet located at sta 150+33.4

Storm water from a one hour duration 100 year storm would be fed into the treatment tank for solids removal and filtration. Water soluble pollutants would not be captured and anything above the one hour duration would be bypassed directly to the creek.

Inexplicably, after collecting and removing the water from the bridge, and feeding it through a hydro-dynamic separator and filter cake to remove solids, the water is discharged to Harrods creek at the Harbour at River Road. The creek flows north back into the well-head protection zone, and a slug of concentrated road runoff will likely sit over the intake area.

In winter and summer, pollutants that are not removed by this treatment train will pool at the outfall in the bend of the creek or slowly migrate out the creek channel to the Ohio.

Often, Harrods Creek flows backwards due to the rising Ohio River and the concentrated pollutants may remain in a slug in lower Harrods Creek, an important freshwater wildlife and aquatic habitat zone.

Backwater areas as nursery habitats for fishes in pool 13 of the Upper Mississippi River

William A. Sheaffer and John G. Nickum

Volume 136, Number 1, 131-139

“. . . backwater areas were judged to be important nursery areas for larval and juvenile fishes, and seemed to benefit downstream main-channel sites. Any loss of these habitats would be detrimental to the Mississippi River as a whole.”

Concentrated road salt solution could collect in the lower backwater reach and infiltrate into the artesian collection system sooner than engineers suspect.

“Heavy metals are among the most important pollutants

in stormwater runoff that are generated by transport activities

(8, 9). These pollutants have significant human and ecosystem

health impacts (10-12).”

Impacts of Traffic and Rainfall Characteristics on Heavy Metals Build-up and Wash-off from Urban Roads

Parvezmahbub, et al, Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 8904–8910

This treatment strategy would not have a KPDES water quality permit but would be under the general stormwater permit granted to the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet or MSD.

Description

A variety of products called swirl separators or hydrodynamic structures have been widely applied to stormwater inlets in recent years. Swirl separators are modifications of traditional oil-grit separators. They contain an internal component that creates a swirling motion as stormwater flows through a cylindrical chamber. The concept behind these designs is that sediments settle out as stormwater moves in this swirling path, and additional compartments or chambers are sometimes present to trap oil and other floatables.

Limitations to swirl separators include:

•Very little data are available on the performance of these practices, and independent studies suggest only moderate pollutant removal. In particular, these practices are ineffective at removing fine particles and soluble pollutants.

• The practice has a high maintenance burden (i.e., frequent cleanout).

“Fourth, chloride, and to a large degree sodium, the two primary ions in road salt, remain in solution, making it difficult with present-day technology to design effective management practices for reduction of road-salt loadings to receiving waters after application. Currently, reduction in usage appears to be the only effective road-salt-runoff management strategy.”

“The presented long- and short-term runoff sampling programs in Wisconsin demonstrate a substantial effect from road salt on streamwater quality and aquatic life. Bioassay results from runoff events confirm that the observed high concentrations of road salt caused acute and chronic toxicity to aquatic organisms. In addition, continuous specific conductance results indicate that elevated levels of road salt were present multiple times per year each year of monitoring. Populations of aquatic organisms in these streams and others with such road-salt influence are likely limited to salt-tolerant

species.”

A Fresh Look at Road Salt: Aquatic Toxicity and Water-Quality Impacts on Local, Regional, and National Scales

Steven Corsi, et al, Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 7376

“Instead, shifts in the composition of macroinvertebrate assemblages suggested that urban stormwater runoff lead to persistant degradation of the chemical quality of the habitat. The significant shift in taxonomic composition of chironomid assemblages suggests

persistent effects of stormwater, probably due to toxic compounds and/or nutrients adsorbed to deposited sediment (Pitt, 1995), although we were not able to measure these directly. Pratt et al.

(1981) also concluded that the effects of urban runoff on stream benthos were mediated via toxic compounds accumulated in the sediments.”

Temporal and spatial responses of Chironomidae (Diptera)

and other benthic invertebrates to urban stormwater runoff

Susan E. Gresens et al, Hydrobiologia (2007) 575:173–190

“The resolved [gas chromatograph] peaks represent various nonalkylated 4- to 6-ring PAHs (high molecular weight PAHs or HPAHs), which are indicative of the combustion-derived particles in engine exhaust (2, 24, 25). The residual range UCM hump is

comprised of (mostly) branched and cyclic hydrocarbons that occur in heavy petroleum (i.e., lubricating, hydraulic, waste oil, and asphalt), which is an expected component within urban runoff (26).”

Comparative Evaluation of Background Anthropogenic Hydrocarbons in Surficial Sediments from Nine Urban Waterways

Scott A. Stout, et al, Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 2987-2994

Test results of monitoring wells located around the Zorn Avenue water company pump station show tremendous levels of chloride contamination in the groundwater.

Engineering studies obtained from the Bridges website show that engineers are planning to dump the east end bridge roadway runoff into Harrods Creek right where the twin roadways pass over River Road.

see: <http://www.kyinbridges.com/project/engineering-information.aspx>

There is no discussion about road salt. Salt does not settle out and would not be removed by the proposed treatment system. The capture capacity is limited to 1 hour duration of the 100 year storm, above that, the tank would be bypassed. There is no discussion of expected pollutant levels that would be discharged to the ugly rip-rap lined discharge outlet into Harrods Creek. Over time the creek sediments would become contaminated with metals, oils and chemicals not removed by the simple settling or swirl treatment designed to remove grit.

BadwaterJournal predicts severe water quality impacts caused by this concentrated collector discharge draining the entire east end bridge deck and approach roadway. No discussion was in the documents that the road salt contaminated water would travel downstream and infiltrate into the well head protection area.

“Section 4 of the Louisville-Southern Indiana Ohio River Bridges Project is the Kentucky East End Approach in Jefferson County for the new East End Ohio River Bridge (Section 5).

Beginning at the I-71 Interchange with KY 841, Section 4 continues in the KY 841 corridor to US 42 (a distance of approximately two miles), where the Mainline tunnels under US 42 and the historic Drumanard Estate for a distance of approximately 2000 feet. Leaving the proposed tunnel in the Shadow Wood Subdivision, the Mainline then crosses Harrod’s Creek and River Road on structure. The new roadway continues to cross open farmland on fill and then ties to the approach structure and eventually ends at Section 5, the Ohio River Bridge in the area of Transylvania Beach on the river.

The Kentucky East End Approach is an approximate total distance of 3.5 miles. The Section 4 corridor is adjacent to established neighborhood developments, the cities of Prospect and Green Spring, as well as several recognized historic districts such as the Country Estates / River Road Historic Districts.”

Lochner Engineering

Section 4 Technical Review Meeting

Stormwater System Design Review Meeting

January 15, 2009

Summary by: Debby Taylor, H. W. Lochner, Inc.

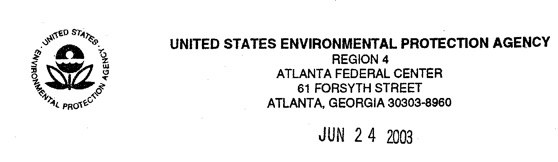

“Under Section 4.1.8

Water Pollution of the Record of Decision, it states:

“Bridge deck runoff shall be collected within a drainage system designed as an element…that includes bridge-deck drains and storm sewers that will transport runoff to the Kentucky end of the bridge. Storm sewers shall be connected and runoff emptied into a storage area designed to hold the one hour peak discharge for a 100-year storm event. The storm water will then either be released to a surface drainage system or pumped into trucks and transported to a facility approved to receive such contents.”

“Discussion followed pertaining to the intent of the statement in the ROD. The consensus of the team was that most pollutants are included in the first flush during a storm event (i.e., the first inch of rainfall). Capturing more than the first flush would involve capturing significant amounts of clean water.

KYTC’s standard procedure for stormwater treatment in a “significant

resource area” (i.e. Wellhead Protection Area) is noted in Design Memo 12- 05, which states:

“Use detention/containment basins to temporarily impound the run-off from swales before it is discharged from the right-of-way. These

basins shall have a minimum volume of 10,000 gallon upstream from each final discharge point.” A water treatment device is included in the present stormwater system that is designed to treat roadway surface runoff flow up to a 100 year storm event in the Wellhead Protection Area.”

In Prospect, the concrete cap of Well # 3 with the buried tunnel following the cleared area back to the drinking water treatment plant. The east end bridge crosses 50 yards south of the cap.

Louisville Water Company website link

http://www.louisvilleky.gov/LWC/News/2010/Riverbank+Filtration+Project+Completed.htm

“World Class Innovation

The project is unique because Louisville Water is the first water utility in the world to combine a gravity tunnel with wells as a source for drinking water.

Louisville Water designed and constructed a mile-and-half-long tunnel in bedrock, 150 feet below the ground surface. The tunnel is parallel to the Ohio River at the company’s B.E. Payne Treatment Plant. Four wells were sunk to collect the ground water and send to the tunnel. A pump station pulls the water from the tunnel and into the treatment plant. Louisville Water can pump up to 70 million gallons of water a day from the aquifer.

Louisville Water began Riverbank Filtration in 1999 with a 15 million gallon per day test well. Extensive water quality research and testing occurred over the first several years of its operation to verify the water quality and the replenishment of the water table. Based on the success, Louisville Water expanded the project to include four additional wells, a tunnel and pump station. The tunnel minimizes the above-ground impact. The wells are capped at the ground and only the pump station at the B.E. Payne Plant is visible above-ground.

A Green Supply

There are several advantages to Riverbank Filtration. Because the water is cleaner, it requires less treatment. The process eliminates taste and odor issues, provides an additional barrier for pathogen removal and creates a stable water temperature of around 55-degrees, resulting in fewer main breaks in the distribution system.

Design and Construction

Construction began in March 2007 and was complete in the fall of 2010. The $55 million dollar investment was funded through Louisville Water’s capital budget. Jordan Jones & Goulding provided engineering and design. Mole Constructors, Inc. was awarded the bid for construction of the tunnel and pump station.”

Winter deicing on the East End bridge and approach will runoff into

the lower reach of Harrods Creek and flow right past the well head protection area of Well # 5. See Road Salt HERE

Above: Two views of a massive salt storage pile at River Road Terminal a few hundred yards from the Zorn Avenue well-head protection zone. River Road Terminal handles salt for bulk materials giant, Cargil.

See <http://www.buddekeww.com/>

Below: The intake pipe for Louisville’s water supply is at the bottom of this building perched in the Ohio River. See the tour pf Zorn Avenue Pump Station

Off Browsboro Road on the other side of the Drummond Estate where the tunnel will emerge, the Shadowood Subdivision homes have been purchased by the state and await demolition to make way for the east end bridge approach.

Where the East End Bridge will cross the river, the homes have been cleared from the river side.

The wetland woods behind the Louisville Water Company settling ponds ring with the cry of wild birds. Soon, the roar of traffic and the dust of particulate pollution will remake the area as an estimated 39,000 vehicles per day pass across the bridge including 4,500 diesel semi trailer trucks.

End of Gene Snyder Freeway at Brownsboro Road

Wellhead Protection area of Louisville Water Company

Above: Historic Rosewell estate near the proposed crossing of the East End Bridge

The Community Transportations Solutions Consultant response did not include an offer to inspect records showing calculated loadings of chloride pollution from the bridge runoff. In addition discharging the polluted runoff during winter deicing conditions would ADD to high chloride concentrations already in Harrods Creek --not be diluted by Harrods Creek.

A further request 2-9-2011 was been submitted for records:

John Sacksteder, PE

Project Manager

Community Transportation Solutions -

General Engineering Consultant

Louisville - Southern Indiana Ohio

River Bridges Project

305 N. Hurstbourne Lane, Suite 100

Louisville, KY 40223

RECORDS REQUEST pursuant to

401 KAR 5:037 Section 7, and KRS 61.872(2) Open Records

These records will not be used for a commercial purpose, but may be included in articles

written for the

<http://www.badwaterjournal.com> website --a non-commercial blogsite.

Dear Mr. Sacksteder,

Thank you for your courteous response, received by email 2-9-2011.

I am requesting to see the design drawings of the bridge approach runoff containment system including the nature and construction of surface ditches or underground pipes, how they are routed and where they go. Since the Bridges Authority and KYDOT will be discharging deicing materials above the WHPA at the East End Bridge site, a groundwater protection plan should be required thatwill contain the requested information.

I am particularly interested in the design and performance specs for the storm runoff

"treatment vaults." I don't think any of this has been shared with any public consultation group--I cannot find any such record. Alternatives to using road salt deicing do not appear to have been considered and your response does not indicate that protection of Harrods Creek extends to calculating the expected chloride concentration of such a discharge from a point source storm water outlet.

Such a discharge would likely exceed 4000-6000 mg/L chloride under winter road salt deicing conditions. Can you address this calculation specifically? The chloride and heavy metal contaminated road runoff would apparently go to detention ponds first, I glean from your response. The location of these ponds relative to the well head protection area is not shown. Will the ponds be lined?

To be clear, I am requesting to view or copies of records:

1) I request to see a detailed location map and engineering drawings that

show the storm water containment system, ponds and treatment vaults

2) I request to see the proposed discharge point to Harrods Creek and any calculated

chloride and metal concentrations for the deicing applied, including the road dust contaminants

of the expected traffic volume in expected winter deicing and runoff storms.

3) I request to see engineering studies calculating locations of detention and discharge

and demonstrating no contamination of the WHPA. Also, the similar studies for bridge

construction pilings and other construction disturbing the area above the WHPA.

My request is not for a few paragraphs of summary from the leadership, but to see records of

engineering drawings and scientific consultations showing that the Bridge Authority has

already commissioned and paid for an accurate calculation of the pollution loadings

that will be generated above the WHPA and has evolved a practical and properly conceived plan to contain and treat maximum expected loadings to protect the water quality --both ground and surface water. If your system does not contain all storms--pollution of the WHPA will result.

I am requesting you add my name to any list receiving notice of meetings of public consultation

of the East End Bridge and WHPA groundwater protection plans.

Thank you for your attention and efforts,

Clarence H. Hixson

Sign in southern Indiana. The issue to a lot of people is whether they have to pay one dollar to cross the new bridges each day.

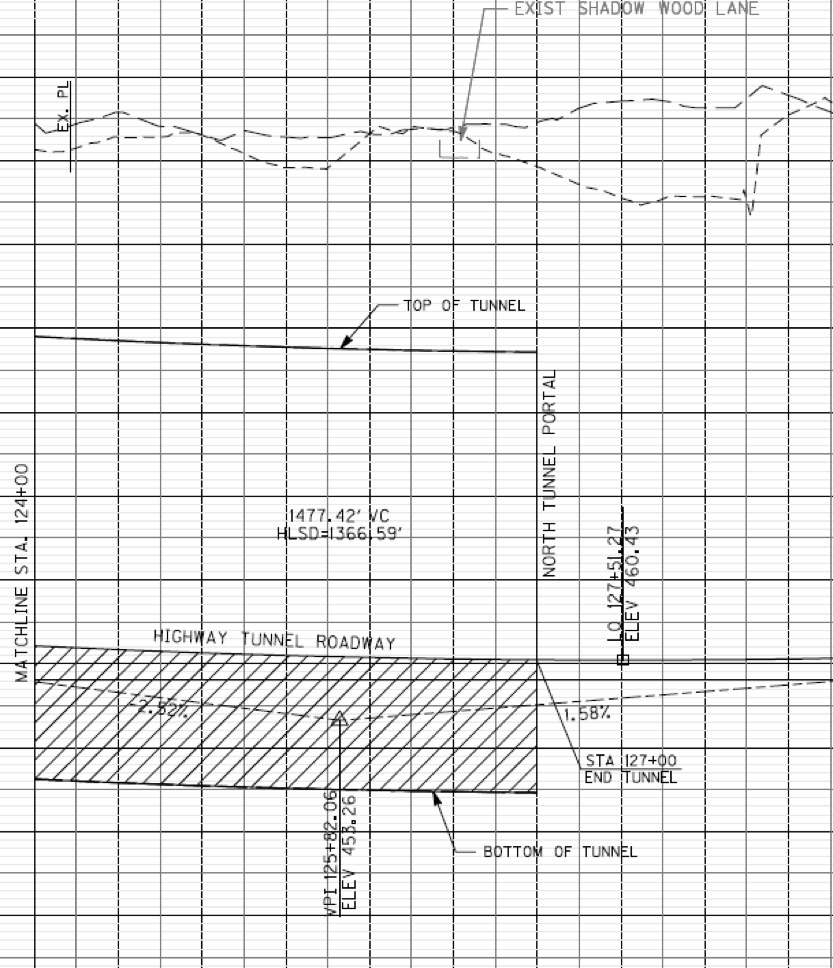

Low elevation point at emergence from the tunnels 460 ft

This drawing shows the main structures of the A-15 selected alternative path for the East End Bridge and Approach highway from Gene Snyder freeway. The black arrow is pointing to the Harrods Creek bridge that will pass over River Road after emerging from the twin tunnels under Drumanard Historic Estate.

The plan drawing above is a section view as it emerges from the tunnel at the lowest elevation between the freeway and new bridge at 460.43 ft.

The road will slope down the length of a mile and a half from elevation of 640 ft at the freeway to 460 ft at the tunnel then back up to 500 ft at the Ohio River edge. 180 feet of rise from the low point means heavier pollution emissions as trucks stomp on the gas pedal to accelerate up the incline both ways.

500 ft elevation at the bridge

640 ft elevation at the freeway

Drawing by Lochner Engineers