July 2003 Report

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION

For the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency

ADDRESSING COMMUNITY CONCERNS: HOW ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE

RELATES TO LAND USE PLANNING AND ZONING

“Environmental and land use planning agencies at federal, state, and local levels

must integrate achieving environmental justice into their missions and make

implementation a part of their core program activities.”

“Environmental justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all

people regardless of race, color, national origin, culture, education, or income

with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of

environmental laws, regulations, and policies.”

Fair treatment means that no group of people, including racial, ethnic, or

socioeconomic groups, should bear a disproportionate share of negative

consequences resulting from industrial, municipal, and commercial operations

or the execution of federal, state, local, and tribal environmental programs

and policies.

Meaningful involvement means that:

-

(1)potentially affected community residents have an appropriate opportunity

to participate in decisions about a proposed activity that will affect their

environment and/or health;

(2) the public’s contribution can influence the regulatory agency’s decision;

-

(3)the concerns of all participants involved will be considered in the decision-

making process; and

-

(4)the decision-makers seek out and facilitate the involvement of those

potentially affected.

-

•Addressing environmental justice concerns is a basic duty of good

government because protecting the health and welfare of the public is

the primary responsibility of effective public administrators.

-

•Leadership and accountability for reducing risks and enhancing

meaningful public engagement are needed at every level of government

to develop solutions to environmental justice problems.

-

•Government at every level has not always been proactive in addressing

environmental justice concerns and citizen protest has often been the

catalyst that prompted government action.

-

•There are many legal and regulatory authorities for federal, state, and

local officials to use when addressing environmental justice concerns,

but they are not being fully or creatively utilized.

-

•More effective coordination is needed between all three levels of

government because each level can contribute legal authorities,

technical expertise, and practical administrative tools needed to

address current environmental justice problems and prevent future ones.

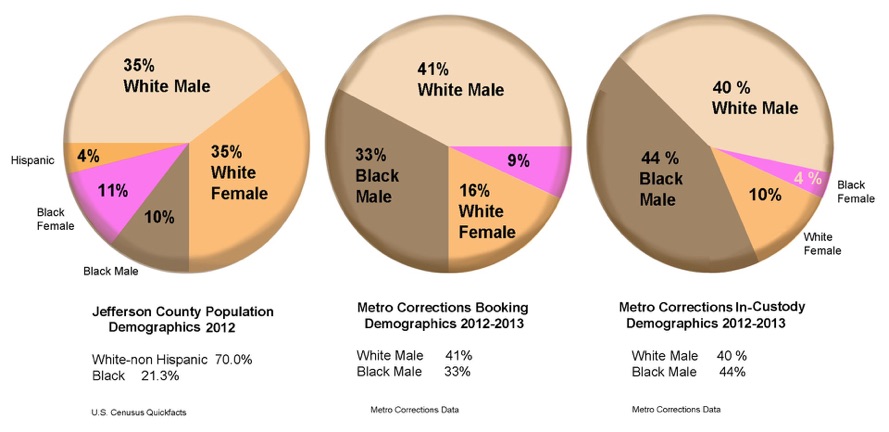

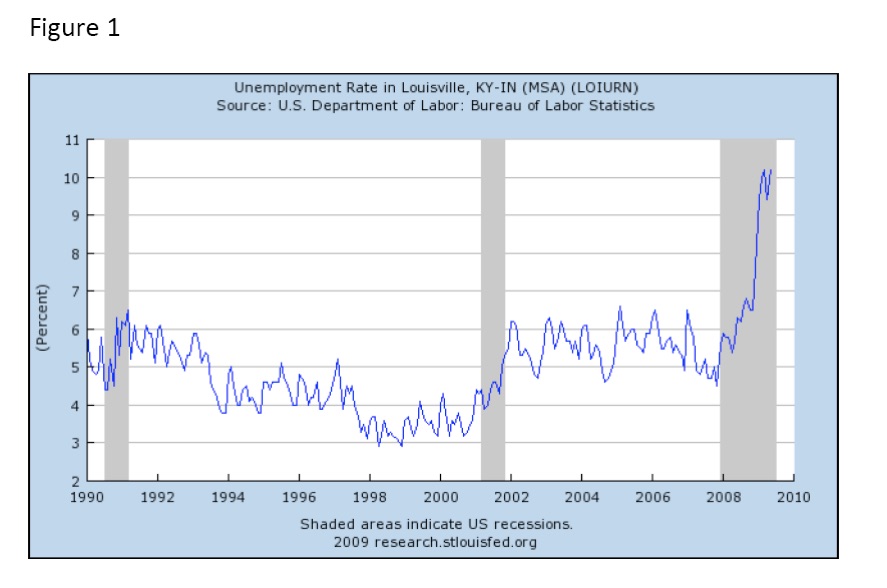

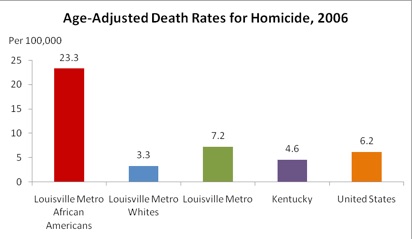

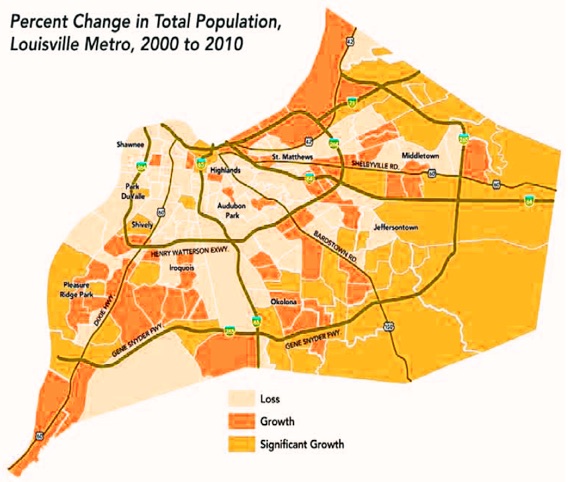

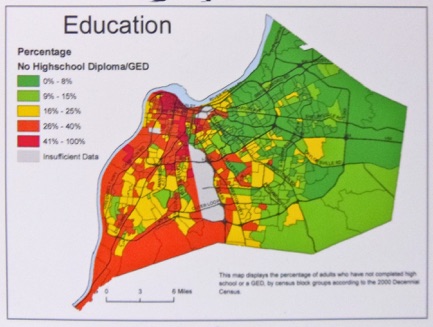

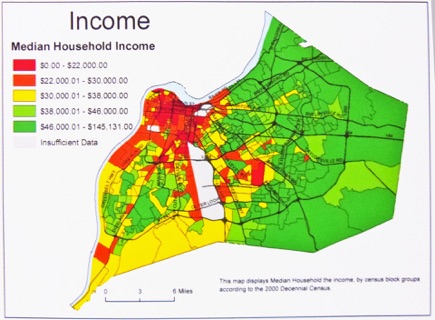

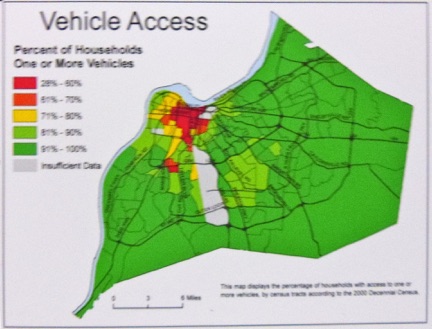

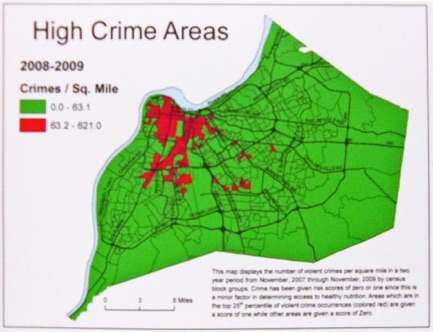

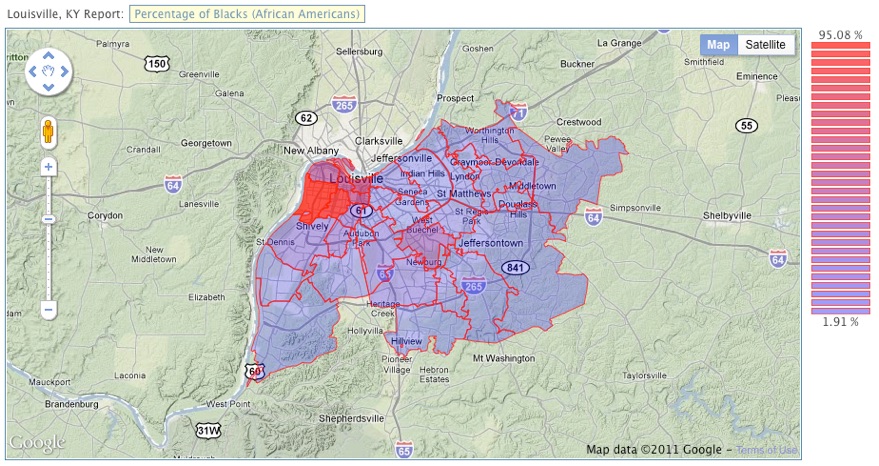

Despite growing awareness nationally of the connection between land use

and social justice, white flight continues unabated in Metro Louisville and

the ring counties. Louisville’s calcified history of racial inequity, preserved in its land use and economic development policies, is used as subject material for college level social justice and environmental health classes.