Welcome to BadwaterJournal.com© INDEX PAGE for all articles

“Today, black Louisville is a community with many leaders in many walks of life, with discordant voices that make noise more often than music, without a shared sense of itself and without a unifying economic, political and social agenda, not unlike black America in general.

However, this is not the first time that black Louisvillians have faced difficulties or suffered setbacks. In this respect, the challenge facing black Louisville today is eerily similar to that facing Washington Spradling and Shelton Morris nearly two centuries ago --how to create, or in this case re--create community.”

J. Blaine Hudson with Mervin Aubespin and Kenneth Clay, Two Centuries of Black Louisville- A Photographic History, Butler Books Louisville, KY (2011).

LET THEM RIDE BUSES

Racist policy once overt, but now cloaked in facially neutral programs

has prevented the formation of unified black leadership in the segregated

West End of Louisville. Recognition of the policy is the first step to ending

the cycle of oppression.

Decades of policy intervention to disempower black people

The story of the struggle for fair representation of black minorities in transportation public policy making in Louisville is one of a still born delivery.

Although KIPDA gives lip service to Title VI compliance, and the FHWA certifies Title VI compliance by the planning organization, its a sham.

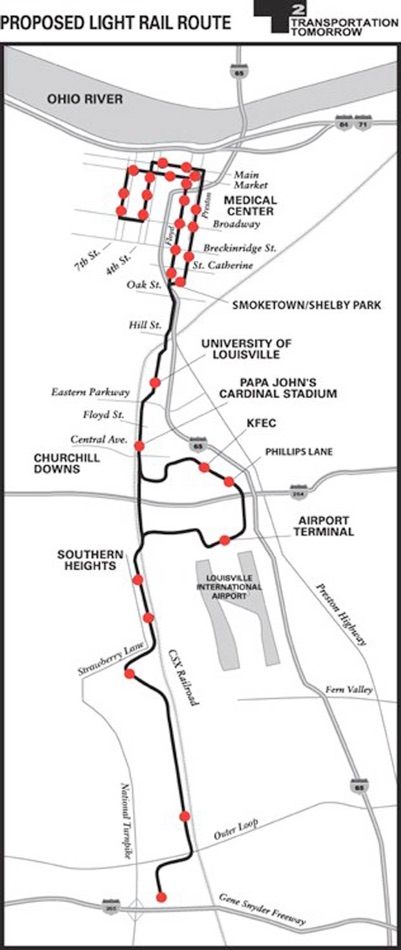

Since 1997 the local public officials appointed to create regional transportation planning have served capitalist enterprise concentrating in the east county over fair and equitable regional planning. A cross-river coalition of politicians decided to cancel TARC’s T2 light rail project that would have connected the west end with suburban jobs.

In this there are echos of the past.

The publication of, Two Centuries of Black Louisville- A Photographic History, by Butler Books presents a readable history well illustrated with photos.

Beginning on page 185 of the Photographic History, the authors give a brief history of the Civil Rights Era in Louisville from 1960-1985.

This era is particularly relevant to the Bridges Project because the civil unrest in Louisville in 1968, with widespread violence, the deaths of two African Americans and arrest of 472 people, was followed by a general exodus of much of the white population remaining in the West End and caused a major drain of business activity from the area.

It began on May 27th, 1968, at 28th and Greenwood with speeches by young black orators against police brutality, but rapidly morphed into a violent suppression by white police wielding batons that created lasting animosities.

In the aftermath of the hot summer of ‘68 the Courier-Journal commissioned the ROPER Research agency to plumb the causes through local interviews. The speakers in the study sound like they walked off the street today--little has changed and in some quarters the community is much worse off today.

Forty five years later the legacy of the ’68 riot has not been healed, and though many of the same complaints existing in 1897 and 1968 are still lingering in the West End today, the angry black voice has been effectively neutralized and turned in upon itself in factional conflict. Literally, a significant number of alienated black youth after decades of being thrown onto the streets in poverty, have turned to violent crime in a no-holds barred struggle for survival.

The racial unrest and destruction of1968 has left economic holes not yet filled. A benevolent leadership coalition intent on making the West End the asset to Louisville it could be is divided between charismatic religious personalities and self serving apparatchiks. Instead of seeing the potential for New Orleans style tourist enterprise based on riverboat heritage, art and music, Metro leaders spend development dollars to build auto industry related suburban industrial parks and sprawl communities.

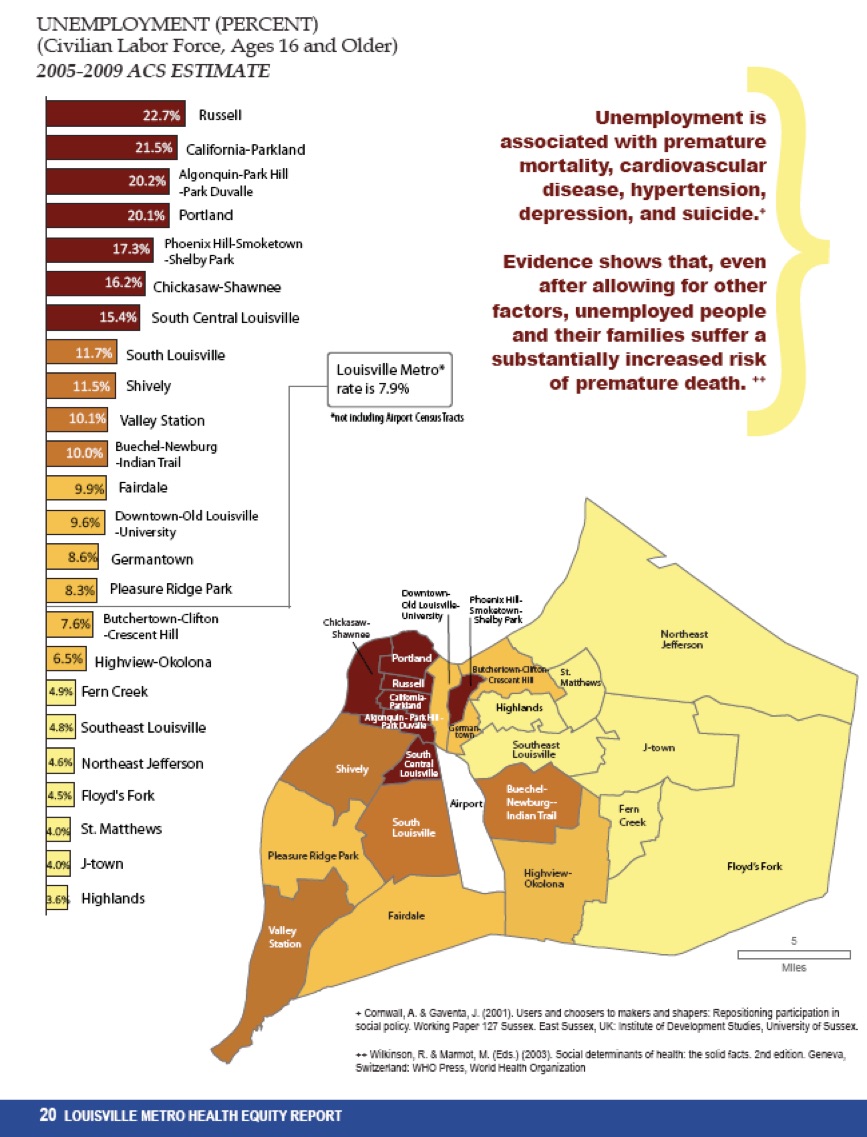

LOUISVILLE METRO HEALTH EQUITY REPORT: The Social Determinants of Health in Louisville Metro Neighborhoods

Patrick Smith, AICP Margaret Pennington, MSSW Lisa Crabtree, MA Robert Illback, PsyD REACH of Louisville, Inc. (Available on the web) page 4:

Structural racism examines racial and ethnic impacts that stem from a history

of disenfranchisement and policies that favored those in power. Consequently, the origins of urban inequality for communities of color cannot be separated from structural racism. An example is the history of

federal housing policies that not only denied homeownership to urban African- Americans but physically destroyed many black neighborhoods under the policies of urban renewal.

Hudson, Clay and Aubespin in the Photographic History, page 196 also describe how “Urban Renewal” utilized as a racist policy by city leaders destroyed the old Walnut Street District that was the hub of the African American Community.

Louisville city leaders moved great masses of black people, uprooting them from community associations under one false premise or another in the 60’s. This malevolent public policy led to the uprising of ’68.

What is chronic and cyclical in Louisville is the uprooting of black communities over and again using building demolition, inefficient transit, and job relocation, as a tool to disrupt community cohesion and prevent economic advancement.

The two bridges plan of the LSIORBP commits $ 10 billion to move economic development away from the west end, deepening the crisis.

On January 7th, 2013 the Coalition for the Advancement of Regional Transportation, a Louisville non-profit, citizen group filed a Motion for trial de novo on its claim the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet is pushing a racist policy in the Louisville Bridges lawsuit. Indiana Department of Transportation INDOT, is also accused.

CART’s Claim is filed in the Western District Federal Court at Louisville, Kentucky. Case number 3:10-CV-00007-JGH in front of Judge John Heyburn. The author of this article is the attorney for CART.

CART’s Complaint

The Complaint language says:

The Complaint makes out more than “bare bones” legal recitals.

¶ 133 summarizes the claim of intentional discrimination that [state] defendants actions approving the SFEIS and RROD was done to intentionally deny CART protected class members and Title VI residents equal participation and benefits in federal funded transportation projects. (Title VI area includes low income African American West End)

¶ 133(a) makes the factual allegation that Defendants purposely formulated a narrow purpose and need statement and used it to eliminate public transit from the alternatives under consideration.

The transportation agencies considered expanding light rail but rejected the option.

¶ 133(b) alleges that after being given a Title VI complaint, the Defendants acted with deliberate indifference to the discriminatory impact of the LSIORBP and formulated a mega project that drained available federal funding from the T2 project, causing a loss of $ 9 million already expended for the EIS and killing the affordable light rail transit project that had particular benefits for the protected class.

¶ 133(c) alleges that Defendants obscured the socio-economic conditions of the Title VI area to avoid addressing transportation needs so as to maintain the disadvantages imposed on the minority population because the crime ridden area is a useful pool of minority disproportionate arrestees to churn through the criminal justice system.

¶ 133(d) alleges the Defendants intentionally discriminated on the basis of race by adopting an unreasonable tolling plan that would disproportionately burden poor minorities for 46 years or more.

¶ 133(e) alleges that the purported mitigations of rehabilitating the Trolley Barn wasted $ 20 million of Transportation Enhancement funds on a project that did not improve personal mobility for the Title VI residents. (West End) The Trolley Barn usefulness for a revived trolley system was destroyed by the rehabilitation and no African American Heritage museum as first proposed was ever installed.

All the above decisions were deliberated at the command level of KYTC and INDOT where Michael Hancock(Secretary KYTC) and Michael Cline (Commissioner INDOT) considered and approved the actions. The same decisions were reviewed and approved by FHWA Defendants.

The legal barriers to succeeding on a claim of intentional race discrimination are significant and many such cases end up wrecked on the rocks of legal procedure and “failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.”

Often there is little or no direct evidence of racist acts by the state officials. Instead, the case has to be built on the history of circumstances.

The history of the West End shows a horrible record of neglect and lack of investment by public officials and private capital. But instead of providing a remedy, the Bridges Project promises 46 years or more of tolls disproportionately burdening poor minorities to build infrastructure with “no significant effect” on employment and the economy of the West End.

In terms of dollars. the main beneficiaries of tolls imposed on all drivers, east end and downtown, will be the economic giants in the east end with a new freight cross river connection to serve their surging automobile manufacturing economy. The greatest amount of traffic will be across the Downtown Crossing whose drivers will pay the lion’s share of tolls.

Southern Indiana local government groups estimate a $ 7 billion dollar loss due to traffic diversion and toll avoidance on their I-65 corridor businesses.

And, the Bridges Environmental Impact Statement admitted:

“In summary, most EJ areas, (environmental justice) including the urban core and West Louisville, are not expected to experience any significant change in employment or household growth rates under any of the "build" alternatives, as compared to the No Action Alternative.”

AR2 _00093658 Environmental Justice Technical Report Addendum Louisville-Southern Indiana Ohio Rivers Bridges Project INDOT DES. No. 9803640 KYTC State Item No. 5-118.00

The Bridges Project by design, leaves West Louisville in economic chaos.

Enough is enough.

During the development of the Bridges Project there were incursions by Republican operatives to buy off dissent and quiet unrest with “faith based” federal grants. $20 million of federal “Transportation Enhancement “ funds was channeled through Metro Government to quiet the complaint of disparate impact in 2002. See story HERE

During the Bush presidency federal grant funds were deployed by Republican operatives like Anne Northrup to fund West End black churches to divide and separate politically active church factions in the West End from the Democratic base.

The longterm effect has been to divide the activist community from its traditional church base and achieve the collapse of grassroots black civil rights organizations militant enough to push effectively for change. See related page Religious Leadership Click HERE

An examination of Louisville’s civil unrest history demonstrates that cycles of outrage are met by repressive political force. However, with the rise of public relations science, political operatives have discovered how to alienate activist groups from mainstream black support and neutralize them.

Dr. Hudson’s quote above gives a true yet depressing observation,

“Today, black Louisville is a community with many leaders in many walks of life, with discordant voices that make noise more often than music, without a shared sense of itself and without a unifying economic, political and social agenda, not unlike black America in general. “

Let it be clearly said, this state of affairs did not happen by accident but by consistent application of a malevolent racist policy operated by top political leaders to suppress self determined activism in the west end,

The white business class acted methodically to buy up, sell out, arrest the poor, undercut and misdirect grass roots black activism for the purpose of ridding public policy decision making of black activism for change. The result, after decades of methodical application of political intervention couched as “faith based” programs, is a West End in ruins, without a powerful unified voice, no independent political representation in the Metro legislative bodies, and no coherent sense of community.

The muscular intervention is demonstrated in the history of the bridges project, particularly in the actions that followed the February 2002 claim filed against FHWA that the project would have disparate impact against minorities, filed by Paul Bather and Jim Wayne. HERE

But, the history of malevolent policy has older roots.

CAUGHT IN THE STAMPEDE, THE $ 450 MILLION DOLLARS NEEDED TO BUILD THE T2 LIGHT RAIL WAS SNUFFED OUT BY THE BRIDGES PROJECT

¶ 48 alleges that the Defendants gave Notice March 7, 1998, they would prepare an EIS including the ORMIS two bridge recommendation.

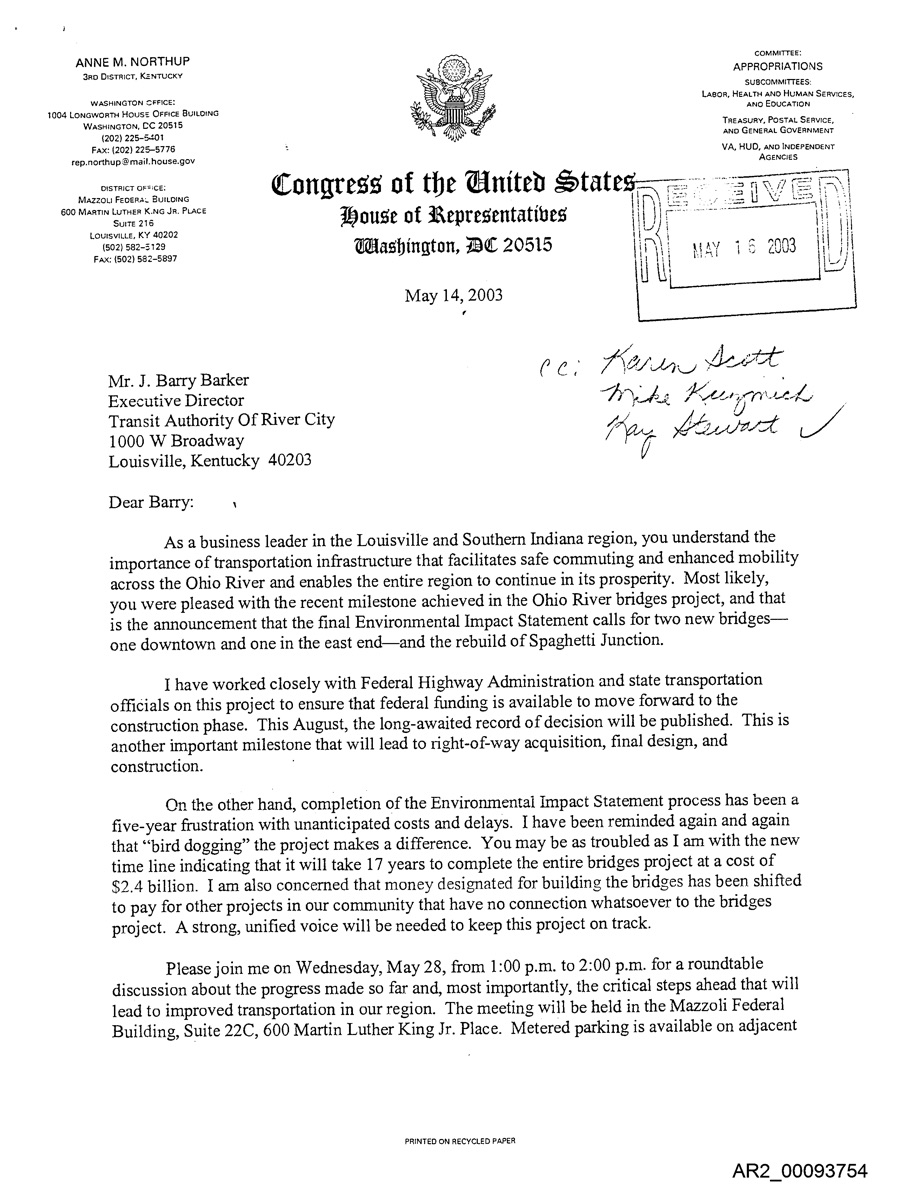

But see, AR2 00124426, 1998 Letter on T2 funding. AR2 00098201 Sept 30, 2002, Letter to KIPDA from Barry Barker requesting $ 20,000 in funds to help prepare the T2 EIS. AR2_00093754.

May 2003 Letter to Barry Barker from Anne Northrup stating she has worked to get federal funds for the two bridges project and the community must speak with one voice.

¶ 43 alleges the fact that on May 13, 2004 then Mayor, Jerry Abramson stated, “the funds are simply not there to build two bridges and light rail.”

WEEDEN’s HISTORY of the COLORED PEOPLE of LOUISVILLE 1897

“WHAT ONE GENERATION HAS DONE FOR A RACE”

“The interests of the Afro-American portion of our population, (not improperly, considering the usual color of his skin, called the Negro), are as numerous' and diversified as are the affairs of his Caucasian fellow-denizen.

Climatic conditions and long established habitat will likely link the destiny of the 'colored race closer in the interest of that portion of our land south of Mason and Dixon's line--to the soil of the newer but no less Sunny South.

The mutual affairs of the two races are so interwoven that which affects the one must involve the other, whether considered from a commercial, proprietary, religious or educational standpoint. So far as property and education are concerned most of the progress in the Negro's prosperity must be dated from the close of the Civil War.

He could not own property when himself was a slave. Then his education was limited to acquiring skill, (giving) remuneration to his master in certain lines of manual labor and to imbibing precepts of abject obedience. When in our market places, in the very center of our public streets human flesh and blood were put upon the block and auctioned off like mules, the public countenance had a check to pride and blush estranged--a curse that palsied the

proprietor as much as it degraded the serf.

Before the war the South had crystalized into a landed aristocracy, the broad acres, with herds of human stock, were in the hands of the select few.

The wealthy white~ relieved of the necessity to exercise became slothful and shiftless. Gratification of the senses usurped the realm of mental activity.

Factories and free-schools were almost unknown. The rich could send their children to the North and the poor grow up in illiteracy. The poor white man could buy no land, for the lords would neither sell to him nor employ him: there were no factories for his labor, nor schools for his children. So it became a saying among the Negroes. “I’d rather be n***er than a poor white trash."

But by the happy termination of the sanguinary strife not only were the shackles stricken from four million slaves but the poor white trash" came in for his liberty too.

The big plantations were chopped up into little farms;

factories sprang up as by magic; public schools were opened, and northern money and muscle swept in like a tide, putting new vigor into the stagnant southern conservatism.

In this shake-up, almost as lively as Biblical resurrection scenes, the Negro--in freedom a stranger, the weak, trembling master of his untried self--turned his first feeble steps on the road to development. Handicapped as he was by years of servitude and want of education, besides the bitter race

prejudice, he moved nervously, slowly but surely toward the front, holding every inch he wrenched from adversity.

But it was only when the school was opened that he began to stand with both feet planted on a rock. The ballot was a

mighty boon; a spear and buckler in the war of civil rights; but only through education could the power of the ballot be efficiently exercised.

With equal law and justice; a free and un-bulldozed ballot: with free, unsectarian schools, the Negro has little more to ask from the public, and must and should now "paddle his own canoe. "

Strength can come only from self-culture, and in the race of social progress the same law applies here or elsewhere--"the survival of the fittest."

A COMMUNITY STUDY AMONG WHITES AND NEGROES IN LOUISVILLE. Conducted for the Courier-Journal

July 1969, ROPER RESEARCH ASSOCIATES, Inc.

“SOME CONCLUSIONS”

There is much that is discouraging in this study, but there is also much that is encouraging and hopeful.

The wide gulfs in attitudes between Negroes and whites on the struggle for Negro equality are very discouraging. Negroes clearly want more and faster progress than whites want or see a need for. And the different conditions under which whites and Negroes live clearly indicate that there is surely need for improved living conditions for Negroes in many respects.

It is encouraging, on the other hand, that in areas where real efforts have been made to improve things for Negroes--education, the opening of public facilities, etc.-- results are shown in that these areas are not seen as real problems by Negroes.

Even more encouraging is that Negroes in Louisville are optimistic and hopeful that attitudes of whites toward Negroes will improve in the next few years, and that they basically endorse a moderate, non-violent route in seeking the changes they desire.

At one and the same time, it is discouraging that the attitudes of white people in Louisville toward the race problem do not appear to provide a fertile climate for changes to take place.

The challenge faced in Louisville, it seems to us, is really the challenge faced by the nation. Changes are needed, but the course must be deliberately steered so that progress is achieved at a fast enough pace to keep Negro discontent below the boiling point, but at a pace not so fast that it outstrips changes in white attitudes and tips whites into further racial bias than now exists.

That this can be done has been demonstrated in the attitudes of both races toward such things as the educational system.

What are some of the things that might help? First, We would think the white citizens in Louisville should be made fully aware of the different conditions under which Negroes live. Perhaps enlightenment will increase understanding. We would also think that whites should.be made aware that Negroes in Louisville do endorse moderate and non-violent methods in their campaign for equality, and do not support the extremists who tend to be newsworthy and perhaps get represented in

the news media out of all proportion to their importance in the Negro community.

We also think it is highly important that somehow Negroes are made to feel a closer association with local government, and for local government to make Negroes feel it is responsive to their needs.

Finally, it almost goes without saying that living conditions for

Negroes should be improved. Two communities living side by side under such different conditions cannot exist without divisiveness. A real effort to improve living conditions would seem to be not only the thing most needed in the immediate future, but also the most effective way to demonstrate to Negroes that their optimism is not unfounded--that things will improve.

In light of both the needs and desires of Negroes for improved conditions, lack of some demonstration by the white community that things are moving forward may result in a falling away by Negroes from their currently moderate positions-- and a larger audience among them for what is now a vocal militant minority.

LOUISVILLE METRO HEALTH EQUITY REPORT: 2012

The Social Determinants of Health in Louisville Metro Neighborhoods

Patrick Smith, AICP Margaret Pennington, MSSW Lisa Crabtree, MA Robert Illback, PsyD REACH of Louisville, Inc. (Available on the web)

Lower income families are disproportionately affected by the absence

of affordable forms of transportation.

Households generally pay around 20% of their income for transportation, but lower income families can spend a much higher percentage of their more limited resources. One study documented that lower income families spend up to 30% or more, depending on the location of the neighborhood where they live. When these researchers looked at the data for 28 Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs), they found that lower-income working families ($20K-$35K) living away from employment centers spent 37% of their income on transportation. Another study found that the poorest fifth of auto owning Americans spend 42% of their annual household budget on automobile ownership, more than twice the national

average.

When faced with high housing costs, many families are forced to make difficult choices, primarily in the area of transportation. Many working families (whose incomes are between $20,000 and $50,000) that move far from work to find affordable housing, can end up spending much of their savings on transportation.

Public Transit & Health

Having an efficient alternative to automobile travel can contribute to the health and vitality of a community. While the lack of such a system can be a source of health risks for everyone, the inability

to access public transit disproportionately affects vulnerable populations: the poor, the elderly, people who have disabilities

and children. People who cannot afford a car or who are unable to drive face a relative lack of mobility options when it comes to jobs, housing, education, social services, and activities.

The relationship between public transportation and access to employment options has been the focus of many studies.

These studies have found significant employment effects from increased bus access and improved accessibility to

employment hubs. In a study focusing on single women receiving public assistance, researchers found that women without an automobile experienced employment benefits from increased access to public transportation.

REGRESSIVE PUBLIC POLICY

It is hard to imagine a worse or more regressive public policy decision in a time of extreme income disparity than LSIORBP.

The Project 2012 Initial Financial Plan, was released July 2012, after the June 20, 2012 Revised Record of Decision approved the project. October 16, 2012, the states released their Bi-State Development Agreement, which on page 40, demonstrates that significant social justice impacts --that should have informed the selection of alternatives in the NEPA process --still remain unknown:

§ 11.4.2.1 The States’ Parties, acting with and through the Tolling Body, agree to: Conduct a detailed assessment of the potential economic effects of tolls on environmental justice populations, using the latest publicly available population data, traffic forecasts, and community input.

Make the results of that study publicly available.

Identify and evaluate a range of measures for mitigating the effects of tolling on low income and minority populations. Provide an opportunity for additional public input on those potential measures.

Approving an alternative that results in increased costs of extraordinary magnitude to the general public and has disparate impacts to the Title VI users violates current EJ policy, FHWA Order 6640.23A, Exhibit 27:

The FHWA managers and staff will also ensure that any of their respective programs, policies, or activities that have the potential for disproportionately high and adverse effects on populations protected by Title VI ("protected populations") will only be carried out if:

1. (1) a substantial need for the program, policy or activity exists, based on the overall public interest; and

2. (2) alternatives that would have less adverse effects on protected populations have either:

a. (a) adverse social, economic, environmental, or human health impacts that are severe; or

b. (b) would involve increased costs of an extraordinary magnitude.

Affidavit of Peter B. Meyer, PhD,

Pres.and Chief Economist, The E.P. Systems Group, Inc.

after Review of LSIORBP NEPA Process Documents and the Complaint of Plaintiff, Coalition for the Advancement of Regional Transportation

. . .

16. The Bridges project is, by the prior admission of its adherents not an overall Economic Development

effort, since the FEIS – on which the SFEIS relies fully for its environmental impact assessments –observes (p. 5-3), with respect to all alternatives including the “No-Action” option, that,

“The regional totals for jobs and households within the LMA for year 2025 remain the same under all alternatives.”

This is an explicit admission that taking one of the proposed actions costing billions of dollars is not expected to promote an expanded local economy in the future.

Logically, therefore, the project either

-

(1)must be evaluated as a transportation project, or

(2) examined as an intentional effort to alter the

spatial distribution of jobs and households within the LMA (Louisville Metropolitan Area).

(a) If the project is purely a transportation project, then the failure to consider fully the costs and benefits of the transportation effects, including those associated with construction as well as future use and those associated with air and water quality impacts, renders this SFEIS incomplete at best.

Section 601 of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000(d) (“Title VI”)

Section 601 of that Title provides that no person shall, "on the ground of race, color, or national origin, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity" covered by Title VI. 42 U.S.C. § 2000d.

CART’s allegation embraces interests within the scope of CART’s organizational interests as demonstrated by its mission statement:

“CART promotes environmentally sustainable, socially just, multi-modal transportation that provides affordable access and regional connections to all race and income groups.”

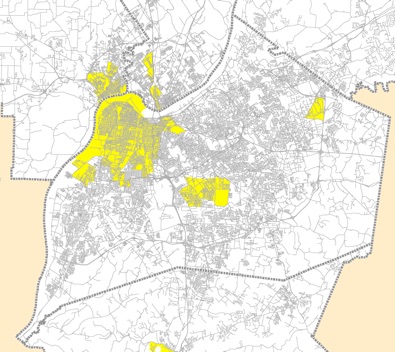

MAP of low income minority “Title VI” area from FEIS

THE 1968 ‘BLACK POWER’ RIOT (excerpt)

Bruce M. Tyler

“A riot erupted on May 27, 1968 as the rally broke up because of a number of very fundamental problems that had gone unresolved. The immediate crisis involved the accosting and arrests of Charles Thomas and Manfred G. Reid. Despite the false rumor, that [Stokely] Carmichael had been detained; it had a powerful affect on the crowd.

There were other deep social community issues at stake. Ken Clay operated a social club at “The Corner of Jazz” and worked for an anti-poverty agency. His Negro art shop was located next door to a pool hall. He noted that 28th Street and Greenwood was a refuge for a few blacks after school or work since they had few social places to go. The Metro Lounge, the Moon Cleaners and the Little Palace Restaurant were the few places blacks had to go in a socially segregated Louisville.

“When urban renewal moved everything out of the Walnut area this became one of the only gathering places for eight or 10 blocks.” He lamented, “There’s just nowhere else to go at night for a bite to eat or a beer.”20 Urban renewal became Negro removal. It destroyed the black central business and social-cultural district on Walnut Street where blacks could cluster for food and drink and social merriment and interaction.

The destruction of Walnut Street left the black community without identity, purpose and direction. The core black community had no social and cultural focus. Ken Clay was part of a new rising social and cultural leadership that attempted to provide that new focus and social site.

Black Louisvillians of all social classes bitterly lamented the decline and final destruction of the old Walnut Street days. James C. Scott’s theory of how weak and dominated groups developed their “hidden transcript” offstage to counter dominate groups allows one to see the crisis that erupted in Louisville. Blacks believed that they had a “privileged site” in the old Walnut Street scene and environs.21 Urban renewal shattered and destroyed Walnut Street and blacks had not revitalized it either. There was no apparent official policy to reconstruct the segregated black social, cultural and community focus that many blacks could discern. The black middle class had not effectively defended or revitalized the Walnut Street society and social sites.

Blacks lost their social and cultural autonomy with the passing of Walnut Street and only memories of its “Golden Age” remained. On Walnut Street, blacks had turned the abusive segregation system and domination with its constant insults and injuries into a positive social and cultural system of “congregation”22 to enjoy their own company, nurture social and cultural life and to affirm each other despite exclusion from white society. They had their social, cultural, and central business district with a felt sense of social and cultural autonomy. Before Walnut Street declined by the late 1950s and the larger black community began to disperse or socially distend by the 1960s, Walnut Street and other black institutions held the black community together. Central High School was a major social and educational institution that also gave focus and cohesion to the black community in the West End.23 Many blacks, old and young, were frustrated, bitter and longed for congregation similar to old Walnut Street. Black power slogans and protest became a new sort of community emerging to strike out at the people, symbols and power elites who had let the black community down as it suffered this new and deepening social, cultural malaise with the loss of the Walnut Street as a social and cultural site. It had served as an autonomous and “privileged site” of ethnic congregation.”

Bridges Timeline begins another cycle of black disempowerment

The timeline on the story dating back to 1996 reveals a lot of information.

TARC initiated its T2 light rail planning efforts,dubbed Transportation Tomorrow (T2) in 1996. Nina Walfoort reporting for TARC wrote about the outstanding public consultation process for T2 involving poor communities in 2002--

“Since 1997, the TARC T2 team has held 282 community meetings,

132 meetings with public agencies, and 162 interviews with key leaders

and stakeholders. Input from these meetings has shaped the project

in significant ways:

◆ TARC signed a partnership agreement with two minority neighborhoods

in the study area—Smoketown and Shelby Park—to ensure

that a detailed neighborhood plan, increased neighborhood employment,

and an economic development strategy would result from the

project. TARC also agreed to work with the neighborhoods to

address such issues as parking, property value increases, and taxes.

This open and proactive approach has made the T2 community

involvement process a model for the region. The local newspaper, The

Courier-Journal, commended TARC for its outreach in a September

1999 editorial, and the weekly publication, Business First, headlined an

October 1999 editorial,“Light-Rail Plan Shows Way To Seek Input.”

But in 1996 other political forces were stirring in KIPDA

KIPDA formed a broad-based (mostly Caucasian) advisory committee, the ORMIS Committee, (Ohio River Major Investment Study ) to guide the study and make a recommendation to KIPDA’s Transportation Policy Committee (TPC), the official decision-making body for ORMIS. ORMIS also incorporated an extensive public involvement program, including four sets of public workshops between December 1995 and November 1996.

In December 1996, the KIPDA TPC unanimously endorsed the recommendation of the ORMIS Committee for a preferred investment strategy incorporating four elements: a “two-bridge solution;” bus-oriented transit improvements; short-term traffic operational improvements; and a regional financial summit to deal with funding needs.

Thus, the ORMIS product attacked the T2 process and killed it.

At the same time ORMIS was proceeding, KIPDA was preparing the LMA’s fourth long-range transportation plan. This plan, completed in 1996 and periodically updated since, is entitled Horizon Year 2020 RMP (Horizon 2020).

1998

The Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) issued a Notice of Intent in the Federal Register on March 27, 1998 indicating that FHWA, in cooperation with INDOT and KYTC, would prepare an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) to evaluate alternatives for improving cross-river mobility between Jefferson and Clark Counties, including the ORMIS recommendation.

In December 1998, the FTA sent a letter to KIPDA saying federal funds were not reasonably available for T2.

2000

In the midst of development of the LSIORBP and the challenge against T2

Republican operatives began to hand out federal grant money to West End churches. The Louisville Neighborhood Initiative was formed by Anne Northup in the spring of 2000 and was initially awarded nearly $5 million in federal funds by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and other corporate contributors. Kelly Downard was an LNI Board member.

“Under the criteria that a faith-based organization be the primary recipient or a major benefactor of an award, the funds were slated for distribution to community churches and other faith-based agencies to provide needed services in poor urban Louisville neighborhoods in the third district. Northup, an LNI board member, said LNI would decide which projects to fund and distribute the monies accordingly.”

The LNI was sued by the ACLU, calling the program a Flim Flam

2002

On February 25, 2002, members of the General Assembly, Jim Wayne and Paul Bather, filed a Title VI Complaint to KIPDA alleging that the two bridges project would cause disproportionately high and adverse impacts to low income African Americans in the urban core, by shifting more economic growth to far eastern Jefferson County and southern Indiana where the population is 85-95% white, higher income residents.

They cited, Savitch and Vogel Consultants, Report 3: Ohio River Bridges Project: Sprawl and Urban Disinvestment, February 2002.

“The wealthiest areas in the Louisville Metropolitan area are growing richer, while poorer areas fall behind.”

Further discussion involved the lack of consultation of urban minorities in the plan preparation, the inability of transit dependent people to access new economic benefits in the east end and the loss of inner city housing and property values from 1970 to 1990 caused by ring development which this project continues.

2003

September 2003--FHWA approves the Louisville Bridges Project coming in a cost of $ 4.1 billion. The high price subsequently required adding tolling as a source of revenue along with bond financing.

2004

Defendants response to the 17 page Title VI Complaint, was not to add a public transit project to the LSIORBP, but to quiet the dissent by providing a $ 20 million in state and federal funds under 23 U.S.C. § 133(d)(2), funneled through Metro Government, to a group of non-profit entities including the African American Heritage Foundation. As set forth in Section 4.3.3 and 4.3.4 page 44 of the 2003 ROD, the funds were used to ‘restore’ the old Trolley Barn at 17th and Muhammad Ali as a Kentucky Center for African American Heritage.

2005-2008

After T2 was abandoned because there were not enough federal funds to build it, the Project sponsors found new funding for the Bridges at a reduced cost of $ 2.6 billion. They would toll the bridges and finance the cost.

June 2012

Project sponsors KYTC, INDOT and FHWA wrapped up the final environmental impact study and approved the tolled project. In December 2012 the Walsh construction consortiums announced they would build both bridges by 2016 for $ 1.6 billion. This reduced price would not have required collecting $ 10 billion over 35 years from drivers and the East End Bridge could have been paid for with available funds without tolling.

2013

Today, CART alleges that transportation officials were motivated by racial animus when they adopted the ORMIS Plan for two bridges and made it the LSIORBP.

To prevail in the lawsuit, CART has to show that the LSIORBP is yet another cycle in the black disempowerment agenda, the chronic dislocation and separation by public policy of blacks from economic means.

Its one more round of the same cycle visited upon the West End populations before by Urban Renewal programs, police riot, disproportionate arrest, vacant property programs and now induced economic development in the far edge of the region out of reach to impoverished blacks in the urban core.

CART was assisted in the lawsuit, without promise or payment by economist, Dr. Peter Meyer formerly of UofL.

The Affidavit of Peter Meyer, Ph.D. ¶ 39 page 24, states:

“FHWA’s SFEIS as it stands recommends that billions of dollars be spent to support those with access to cars while no additional spending serves those without such access despite evidence of poor transportation access for that population. Statistically, the latter are predominantly low income and minority group members. Thus the entire project is inherently discriminatory against those groups.”

Indeed the transportation agency defendants admit there is no economic benefit to the West End in this, the costliest project ever undertaken by KIPDA and the transportation agencies:

“The assessment of potential long-term economic effects was based on a detailed and comprehensive analysis which is available for inspection as part of the Socioeconomic Baseline Report at the local project office. The results of that analysis demonstrated that

construction of any of the "build" alternatives—whether a downtown bridge, an eastern bridge, or both--would not have a substantial effect on the economic vitality of the urban core or West Louisville, which contains the largest concentration of minority and low income individuals in the LMA.”

AR2_00093664

The modern populations digitally connected today and reaching across color barriers to create joint actions to change the policy of black disempowerment waged against the West End need only emerge in self-aware grass roots action groups and begin to raise their voice in the public forum.

The present constellation of politicians, many of them in office for decades, have crafted by intent and misdirection a major infrastructure project that is predatory on low income minorities especially. See it HERE

Change will only come through a coordinated movement, a strongly secular movement recognizing that many powerful church based voices have been deliberately targeted and favored with federal grant programs and especially courted to deny their power to those opposing cycles of suppression through facially neutral government programs.

Dr. J. Blaine Hudson would have been a powerful asset in the coming struggle.

INDOT and KYTC officials answer Metro Council Transportation Committee questions Story HERE

NATIONAL JOURNAL JULY 2003 ARTICLE ON

ANNE NORTHRUP

<http://www.nationaljournal.com/pubs/almanac/2004/people/ky/rep_ky03.htm>

“Despite her votes against spending generally, Northup has used her seat on Appropriations to bring in what she estimated in 2000 as "approaching $500 million" into her district--a "fair share" she called it.

In 2001 she got $25.8 million in earmarked projects. She earmarked $3 million in projects for St. Stephen Baptist Church and New Canaan Baptist Church.

In 2000 she set up a group called Louisville Neighborhood Initiative and earmarked $2 million in 2001 and $3 million in 2002 for it, to be distributed by the organization. LNI, on whose board she served, decided to give $600,000 to Cable Missionary Baptist Church for a family center, $350,000 to Mount Olive Missionary Baptist Church to build a neighborhood center and $200,000 to Catholic Charities for senior citizens' housing.

In February 2002 the ACLU sued LNI for limiting its grants to faith-based organizations. LNI dropped that limitation in April. Common Cause charged that by steering money to an organization she was connected with, Northup violated House ethics rules. Northup said she had gotten oral clearance from the ethics committee, but in May 2002 stopped LNI disbursal of grants and went back to earmarking to specific organizations. Democrats charged that Northup was seeking favorable political treatment from black ministers and their congregations. Her response: "From the first day I was elected, I have tried to help the disadvantaged and the most distressed areas of my community. I know where to put money if I want political benefit from it. I know where the swing neighborhoods are. It is not the West End."

Northup's biggest project in dollar terms is the building of two new bridges over the Ohio River, one downtown which would also replace the "spaghetti junction" intersection of Interstates 64, 65 and 71, and one in eastern Jefferson County. At $2 billion, this is the second biggest pending highway project in the nation, after metro Washington's Woodrow Wilson Bridge, and she worked with Indiana Democrat Baron Hill to promote it over several years. She favored building both bridges at the same time, lest the eastern bridge be delayed indefinitely, and DOT prioritized the project for accelerated environmental review in October 2002.”

The SFEIS is further damaged by failure to adequately consider the effects on VHT, VMT, and VHD of already evident and projected changes in fuel efficiency and associated operating costs as well as possible changes in fuels themselves.

(Depending on how and where electricity is generated, for example – or how natural gas gets used a a fuel for mobile uses – emissions and their impacts on neighborhoods could have very different impacts than those now projected and objected to by CART.)

(b) If the project is an intentional business and household relocation effort, then the Bridges project itself is suspect on the grounds of

-

(i)discriminatory intent relative to protected populations

(poor and minority residents),

-

(ii)promotion of potentially environmentally damaging development, and

-

(iii)the SFEIS failure to demonstrate any net benefit to the totality of businesses and citizens of the LMA from the intended relocation impacts.

The economic evaluation fails to conform to the most fundamental economic analysis practices established by the profession: the use of unbiased data that do not, in and of themselves, assume or bias the analysis toward one of the action alternatives examined.

Therefore, the conclusions of the SFEIS and RROD are incomplete and thus unreliable, and the selection of an action alternative based on the assessment conducted is inherently flawed and potentially biased.

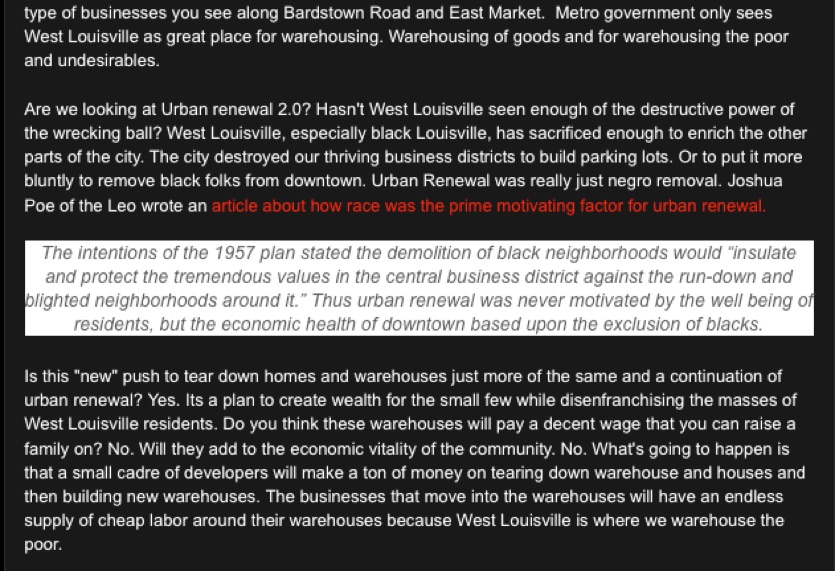

Poverty in Louisville as a desirable condition for Metro Government expansion

See, Haven Harrington blogspot http://urbanlouisville.blogspot.com/

Urban Renewal 2.0

unemployed

jobs